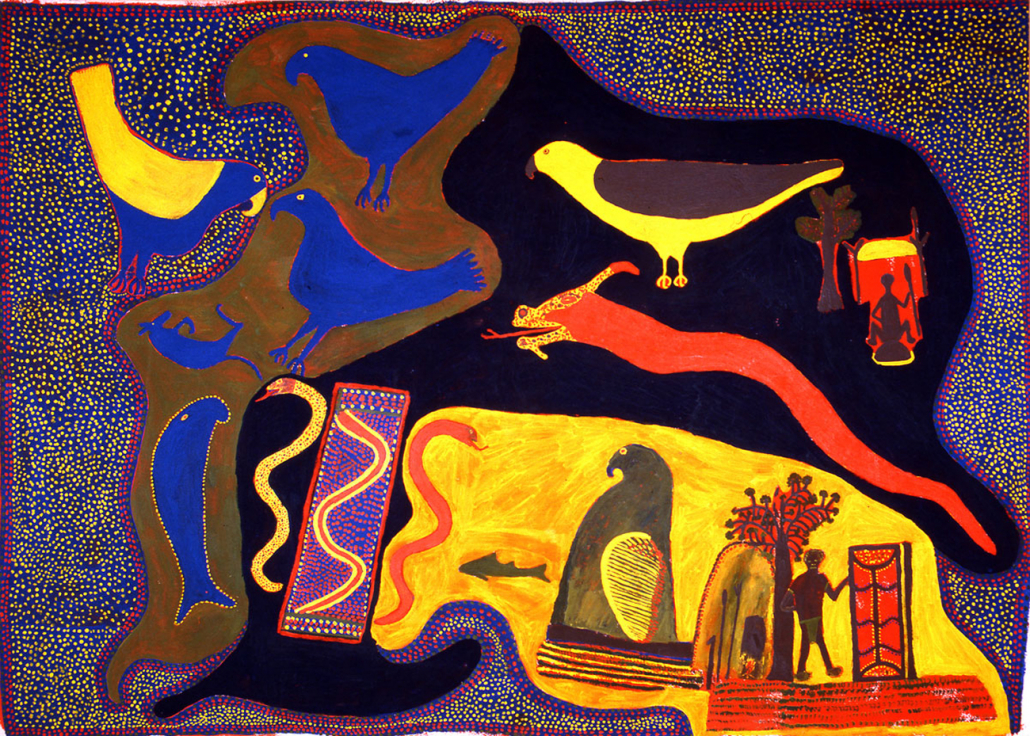

Image: Ginger Riley Munduwalawala, ‘Mara Country’, 1988, is one of the artist’s first paintings of heroic scale that tells the entire story for which he is responsible – his mother’s country around the Limmen Bight and Limmen Bight River in the Northern Territory.

Perhaps his most comprehensive and detailed composition of this size, Riley has drawn together many of the vibrant icons of his country: Bulukbun the fierce fire breathing serpent-dragon, Ngak Ngak the white-breasted sea eagle, the shark’s liver tree, Jatukal (plains kangaroo) and Yulmunji the shark.

The painting is a true celebration of colour. Colour itself was a discovery that opened Riley’s mind to paint large-scale landscapes to depict his mother’s country and this use of colour was inspired by a chance encounter with Albert Namatjira’s watercolour landscapes as a teenager.

‘More than a tree’

Andrew Collis

Flora & Fauna Sunday, Season of Creation

Job 39:1-8,26-30; 1 Corinthians 1:10-23; Luke 12:22-31

God addresses Job, drawing his attention to a Wisdom inherent in the Mountain Goat and the Deer and their birthing practice, the manner in which their young become able to care for themselves; a Wisdom inherent in the free roaming of the wild Donkey as it forages for green grass; in the flight of the Hawk to the south and the nesting and preying habits of the Eagle.

The divine speech stirs Job’s imagination and equips him to recognise his own limitations.

First Peoples have been imagining, or dreaming, harsh and beautiful landscapes for 60,000 years or more. In his book, Dreamings, social anthropologist and linguist Peter Sutton describes travelling downriver in northern Australia with a group of Indigenous people when one young man indicates the landscape all around and tells him, “epama epam”, “nothing is nothing”. The world was created by, and is still sustained by, the Dreamings, and all that we see are the marks they have made – everything is imbued with meaning.

In Aboriginal thought, a dichotomy between the physical existence of the landscape and its internal story, its meaning, does not exist, but a post-Enlightenment European sensibility finds this difficult – nature is there to be named, measured, quantified, used; it is food and fuel for our own desires.

Many, for instance, see the fauna as “dumb animals” and yet they are prophetic. Jesus says: “Take a lesson from the Ravens … [D]o not be so absorbed by the worries and cares of life as to neglect what is really necessary: relationship with God … a communion of saints, holy creatures and holy things … a kin-dom of heaven on Earth, in the Earth …”

We can observe the natural world and see how it is tended by a gracious love and care. The examples cited in the gospel involve creatures considered “dirty” (the Raven, like the Ibis here in Waterloo and Redfern, is a scavenger); beings powerless, fragile, beautiful (lilies and flowers of the field); beings fleeting and transient (as grass).

We are given evocative phrases to engage our imaginations: “more than food”; “more than clothing”; “more (to) value”; “more (to) caring” …

I think of the landscape paintings of one of my favourite artists, Idris Murphy, for whom a tree is always more than a tree. It is part of a living and moving world – in relation to the sky and soil, the birds and animals at home with and within it; in relation to light, colour and shadow, the “alive-ness” of the picture, the memory and creativity of the artist, the Holy Spirit. “The tree is no impression … but is bodied all over against me and has to do with me, as I with it – only in a different way.”

The gospel paints a picture of providence. We are asked not to worry about food, drink and clothing, but to strive for communion, the kindom. “We are called to be sensitive to and live in sync with the prophetic Wisdom of the fauna and the Earth and discern within such biodiversity the Wisdom of God” (Monica Melanchthon).

It is essential that we recognise our “creatureliness” and an inextricable link with the rest of the Earth and its creatures. This is not pantheism. It has to do with the otherness of creatures (“non-human persons”) and the together-ness of life on Earth.

The suffering love of Jesus – the Holy Cross or Tree – connects human beings in a Spirit of compassion. In the same Spirit, the Cross/Tree connects us with all beings who experience suffering, and, in their own ways, persevere, strive, live and love.

The apostle Paul sees that the Cross/Tree is key – that its meaning cannot be measured in terms of mere human wisdom. From a conventional perspective, the suffering of the weak – including trees and animals in bondage or at the mercy of human needs, desires and projects – is unfortunate, tragic. It can be a sign of real Wisdom, however, and it is, says Paul, for those who believe – that is, for those who experience compassion – existential and expansive, holistic and immersive.

The connection to landscape that Murphy tries to express in his work takes inspiration from Aboriginal painters such as Kimberley artist Rover Thomas and southeast Arnhem Land artist Ginger Riley Munduwalawala (known as the “boss of colour”).

Murphy’s work also draws on ideas proposed by the Jesuit poet Gerard Manly Hopkins, in particular the explanatory writings of his invented category of experience, “inscape”, which he uses to “personify” all of nature’s subjects. These include “transcendence”, “the soul of art”, “the charged presence of the Creator in all forms of creation” and a unified complex of ideas associated with the expression of “the inner essence of an object”.

We too can know this saving power and Wisdom.

Murphy writes: “I do what the painting suggests or gives me. It’s an interactive process.”

The Season of Creation invites human believers to join in worship with a diverse flora and fauna family. “All our kin living on this planet, from the Pine to the Eucalypt and Boab, the busiest Bee to the tallest Giraffe. We remember our ancient relatives who became extinct … We join our siblings in praising God … We summon the kin we have come to love … Sing, family, sing!” Amen.

Idris Murphy (b. 1949), ‘Mornington Morning’, 2013, acrylic on paper.