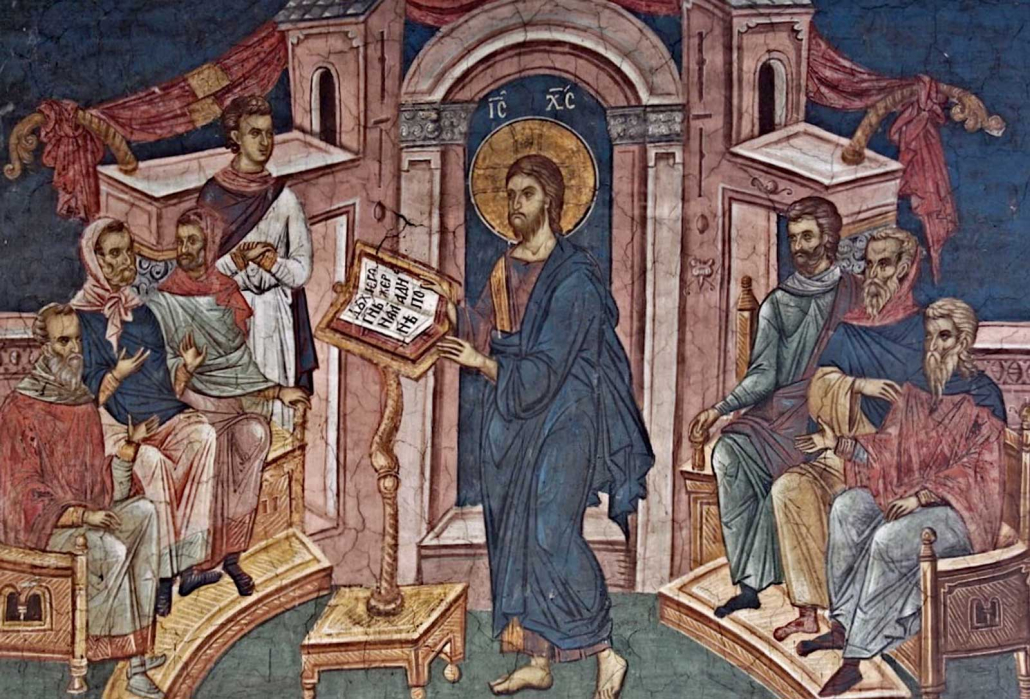

Christ in the Synagogue at Nazareth (Anglican Way Magazine).

‘Love and release’

Andrew Collis

Epiphany 4, Year C

Luke 4:21-30

As we heard in the liturgy last week, Jesus stands and reads from Isaiah 61, omitting a reference to divine vengeance (Isa. 61:2b) and adding a phrase to do with “release” (from Isa. 58:6; see also Lev. 25:10). Jesus reads deeply/creatively.

Moreover, he owns what he reads and understands as a claim upon his life – as a call to messianic speech and action – messianic peace (wholeness, kinship, community …).

We might say that Jesus accepts this Spirit of love (non-vengeance) and release (forgiveness/healing, liberation/freedom from diabolic and social chains) as the guiding force and purpose in his ministry, as the meaning to his life – his vocation.

“The Spirit of Our God is upon me:

because the Most High has anointed me

to bring Good News to those who are poor.

God has sent me to proclaim liberty/release to those held captive,

recovery of sight to those who are blind,

and release to those in prison –

to proclaim the year of Our God’s favour.”

We note that his sense of vocation, his giving expression to it, is compelling/attractive. At first, the members of his home synagogue in Nazareth respond positively. Perhaps they appreciate his confident manner (such a short homily) or sonorous tone.

Appreciation turns to scepticism, though (“Surely this isn’t Mary and Joseph’s son!”), before further elucidation from Jesus – citing prophetic ministry to outsiders as inspirational examples of love and release – provokes indignation and hostility.

Brendan Byrne SJ writes: “[T]his all-important scene serves a two-fold function in the Gospel. It establishes once and for all that the heart of Jesus’ message is the good news of acceptance, the invitation to all to come and be drawn into the hospitality of God. It also shows how this broad, inclusive outreach will meet with resistance and rejection on the part of those reluctant to undergo the conversion required. The prophet who comes as visitor offering the hospitality of God himself meets with inhospitality and rejection. But rejection does not have the last word: it, too, can be drawn into God’s saving plan and made to further, rather than restrict, the outreach of grace.”

That reference to rejection not having the final word comments upon verse 30: “But [Jesus] moved straight through the crowd [of murderous congregants] and walked away.”

Like many commentators, Byrne finds allusion here to resurrection. Our Collect puts it nicely: “[T]hrough Jesus Christ, whom hatred cannot touch” (Steven Shakespeare).

There’s much we could explore regarding prophetic ministry and inspirational/provocative examples of love and release. Concern for long-suffering refugees as well as (over) professional tennis players. Concern for the consequences of climate change – concern for vulnerable inhabitants of reef and bush – as well as (over) mining magnates, tourists, politicians …

Concern for the wellbeing of prisoners in Australia’s hottest prison. Concern for survivors of colonial violence re-traumatised by jingoistic white nationalists …

We can also reflect a little on vocation. Again, for Jesus, these key terms: love and release.

Blessed life as overcoming violence (including the fear and hatred, the self-hatred, at the root of violence). Blessed life as transcending narrow identity (parochial belief and behaviour).

Love and release means kindom revealed/celebrated. Love and release means wealth redistributed – forgiveness, healing, wholeness, acceptance. Love and release means recovery of sight/vision/wisdom. Love and release means ministry/care for all, especially those denied status, excluded or disadvantaged …

How do you experience your vocation (God’s call upon your life) as a call/pull away from vengeance (blasphemous blame, hostility)? How do you experience your vocation as a means of (offering) release? As a visionary power – bringing clarity of purpose, imaginative capacity, openness to light and beauty? As blessed life with and among the poor?

According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, love is the fundamental and innate vocation of every human being (CCC, 2392). And while, traditionally, there are four categories of vocation – marriage, single life, priesthood and religious life – these are emblematic of diverse and wonderful ways of life. Your specific calling is unique to you.

Still, these key terms: love and release. How might we experience our diverse vocations in terms of love and release?

How, as committed life partners? How, as friends? Neighbours? Guardians, uncles, aunties? Siblings or cousins? Lay or ordained ministers? Writers? Doctors?

The blessed life of a grand/parent in terms of overcoming violence (including the fear and hatred, the self-hatred, at the root of violence). The blessed life of an uncle or aunty in terms of transcending narrow identity (parochial belief and behaviour).

As a teacher, one learns love and release – in revelation/celebration of God’s kindom. As a sister or brother, one practises love and release – in redistribution of wealth and opportunity – life lessons in forgiveness, healing, wholeness, acceptance.

As a writer or musician, activist or scientist, one heralds love and release in recovery of sight/vision/wisdom. As a carer, one champions love and release in company with all those denied status, excluded or disadvantaged …

Finally, how might we, together, experience our vocation (God’s call upon our common life) as participation in Good News for the poor? Through Jesus Christ, whom hatred cannot touch. Amen.