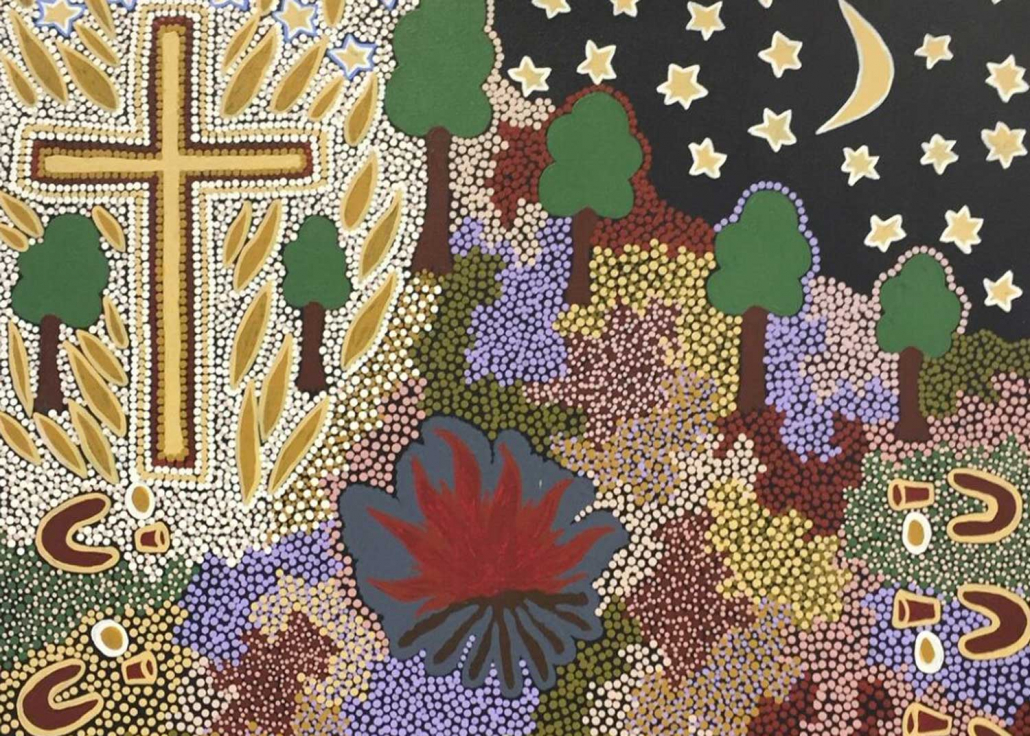

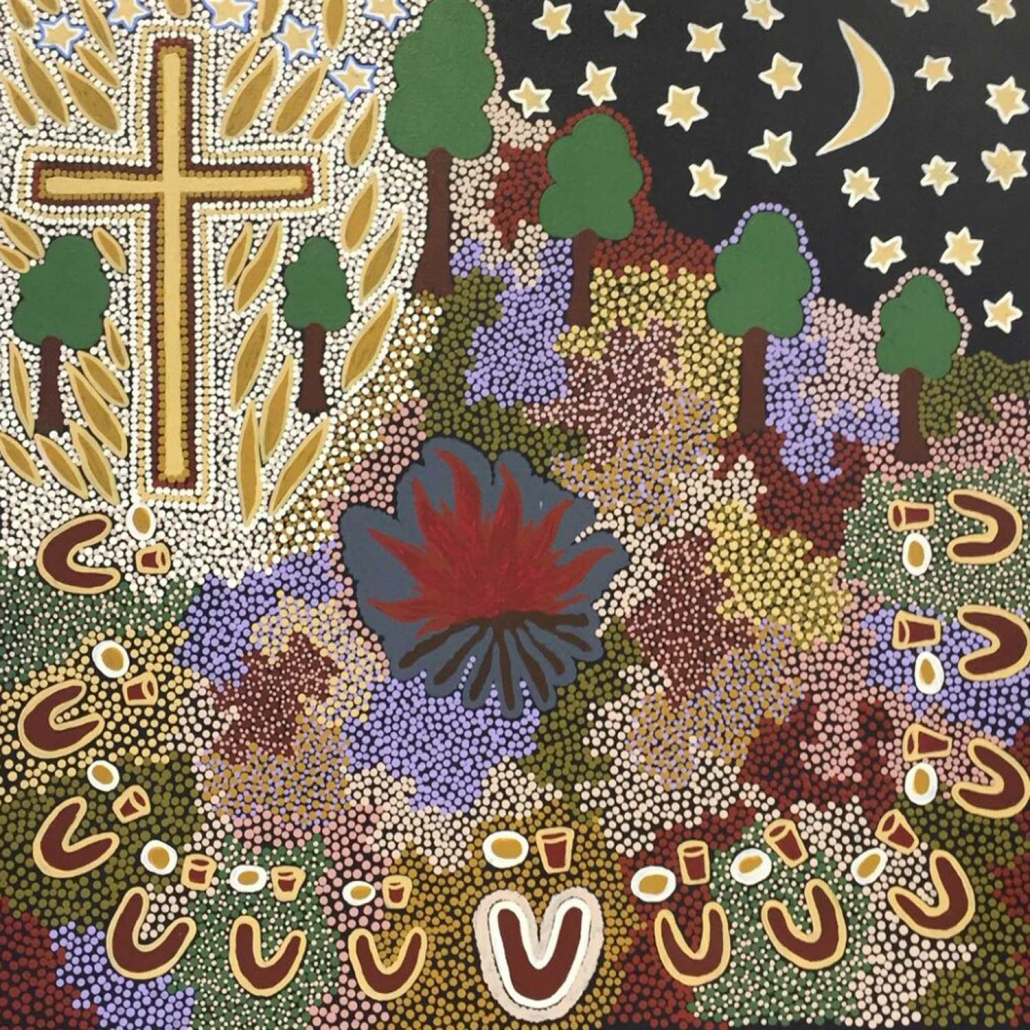

Image (detail): Aunty Lucy Waniwa Lester’s artwork The Last Supper. Supplied by Karina Lester and the Bible Society.

‘Covenant – promise, action, interaction’

Bible study prepared by Andrew

November 2022.

Sunday November 6, 12-1pm.

See conversation notes below.

Thursday November 10, 7-8.30pm.

All welcome. At the manse or via Zoom.

Join Zoom Meeting

Meeting ID: 858 1336 0721

Passcode: 032351

Deverell’s paper was given at the Walking Together: How Can the Church Embrace First Peoples’ Theology in a Post-Colonial Australia conference, Wesley Conference Centre, October 22, 2022.

Key texts: Philippians 2:1-11; 2 Corinthians 8:9-15.

Themes: colonial heritage; justice, redress, imitation of Christ; kenosis; right relationship, partnership; kairos, life; Indigenous theology

Introduction

The author is a Trawloolway man, connected to the north-east of Tasmania. An Anglican priest, he is Lecturer and Research Fellow in the School of Indigenous Studies at the University of Divinity, Melbourne, and the author of Gondwana Theology.

Colonial legacy

Deverell begins by reminding the churches of their colonial legacy.

The churches participated in, and still benefit from, the stealing of First Nations lands.

The churches have blood on their hands because those who participated in the massacres, the frontier conflicts, the genocidal policies concerning First Nations people, were overwhelmingly Christian.

The churches took the lead in the attempted destruction of First Nations spirituality and way of life, especially during the missions period.

The churches participated in, and continue to be largely silent in the face of, the ecocide which accompanied the genocide.

Many churches and members continue to deploy an imaginative terra nullius regarding First Nations people by effectively pretending “we don’t exist”.

“There continues to be a lack of curiosity about our theology,” he writes, “which is different from your theology in fairly fundamental ways.”

The paper raises a fundamental question: how are the churches to reckon with this colonial heritage … and makes appeal to the Pauline tradition, firstly the kenosis passage/hymn in Philippians 2.

Kenosis

Deverell’s comments on the passage are striking.

“Notice a number of features about this passage. It is addressed to a group of Christians who are divided, one against another, who are selfish – who look out for their own survival and wellbeing at the expense of others …

“The Apostle then contrasts this behaviour to that of Jesus – who, though enjoying a certain ascendancy in the cosmic order of things, empties himself (kenosis) of all such power and privilege in order to come among human beings as a slave who has no power at all (doulos).

“The passage then creates a model, a pathway, which Christian communities are encouraged to imitate and follow in order to be truly alive and vital. It is the path of ‘kenosis’: a dying in order to rise to a rather more elevated – more other-centred – mode of being; a dying to all that is power-over, power-acquisitive, power for self alone; and a rising to power-with, power-giving, power for the wellbeing of others.”

Deverell’s commentary on 2 Corinthians 8 is equally challenging.

“The context here is that there are two church communities: one that is very poor and another that is quite rich … We’re talking about money and property …

“[T]here is no hint in this text that the rich church gained its riches by stealing its wealth from the poor church. But, this being so, how much more ought the colonial church consider the ways in which it might return its stolen resources to the people from whom they were stolen?”

Invitation

His invitation to congregations is twofold.

“Contribute 10 per cent of your annual budget to ministries run by Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people, for Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people, in perpetuity.

“Whether there is a denominational agreement for lease-back of properties in place or not, approach your local mob with the question: Could we form a relationship with you that includes your use of this space for community gatherings and programmes without fee or compensation?”

Response

At this point, we noted the following.

Our acknowledgement of Country might include a prominent plaque at the front of the church building. The Metropolitan Land Council might be approached regarding local artists and an authentic visual expression of Gadigal sovereignty. Nathan Tyson at Synod is a key contact, too.

A map of Australia showing First Nations might be framed and hung in a prominent place, to increase awareness of diverse Indigenous cultures, connections, languages. (We have a map at the manse.) Alternatively, the map might be laminated so we can use it in a more interactive way (thanks to Karen for this suggestion).

In respect of the SSH, conversations with the City of Sydney and Aunty Norma Ingram regarding a series of articles by First Nations leaders/writers and image-makers might include prioritising the appointment of a First Peoples editor (a long-held desire of the working group).

In respect of Eden Community Garden, conversations with Clarence Slockee around native plants, trees, “bush tucker” and medicine might include Dharug names for garden beds and other features (mosaics, murals), and, importantly, an invitation to Indigenous groups and individuals to make use of the garden as they wish/need.

Are there opportunities to invite First Nations people to join the SSH working group, the Garden working group, the Arts working group …? To participate in conversations regarding the future … regarding partnerships and possible amalgamation?

In respect of our Arts ministries, could we ensure that at least one exhibition each year is curated by a First Nations curator/artist?

Are there First Nations community groups in need of space or resources we might share … including space in the SSH (print, online, socials), in the garden, studio, hall and church?

ABNER: It is confronting. The history of colonial violence intersects with my own family history. Daring to imitate and follow Jesus means that we will experience some fear and discomfort.

KAREN: For many non-Aboriginal people, First Nations people have not been visible, on the radar of our daily lives. It’s not so much that many of us are not wanting to know more about and get to know First Nations people. It is a matter of creating opportunities to build relationships. I have loved having these opportunities through my involvement with Aboriginal women in custody, through visiting and accompanying them as they undertake different programs.

JANE: Learning words in the Dharug language, as we have in some way already, in our liturgies, opens up possibilities for understanding. Remembering that there are many Indigenous language groups, many First Nations.

ALISON: I’d like us to keep talking about this. It’s about deeper relationships and fuller expressions of the gospel … we shouldn’t just make plans but should always seek relationships.

ANDREW: We acknowledge the hard work and faith of those who built the church here 150 years ago. That’s half the story. We might also acknowledge that the land was stolen, a grant from a colonial government … also that the architecture of the church, the sandstone façade especially, expresses a certain colonial (gothic) notion of transcendence …

As we redevelop the site, the garden especially, how might we supplement this gothic symbolism – there are so many opportunities to do things differently – with other symbols and expressions of the sacred, celebrations of Wisdom … in consultation and in partnership with Aboriginal neighbours, friends … with “local mob”.

ADRIAN: Remembering that the late Richard Green’s scholarship offers resources in Dharug language learning. Blak Douglas created a series of Gunyadyu comic strips for the SSH, introducing readers to words in the Dharug language. Could we revisit this?

KAREN: It’s important that we honour First Nations people in the congregation, including Uncle Keith Douglass, Aunty Val, Aunty Pearl … whose acknowledgement of Country prayer and ritual (placing of sticks from Gadigal land) are central in our liturgy.

CHRIS: The Bible says that love of money is the root of all evil.

ABNER: We could contact Garry Deverell and ask him for further comment/advice … maybe once we have woven new commitments into our mission plans …

MIRIAM: Garry talks about giving 10 per cent of income for ministries run by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. As well as making space in our programs, the call goes beyond this, to relinquish control (kenosis). It is not only about our ministries. What about their ministries?

Beyond decisions made by congregations, Garry challenges denominations to hand over properties and resources to local mob and Indigenous ministries. Recognising our agency in the structures of the Uniting Church, what might we explore in relation to the four properties over which we have “stewardship”, not only our church building?

Decentring ourselves and being open to the mission of country with human community is ecumenical in the broadest sense. What can we learn from others who are on this journey, beyond the Uniting Church?

I am conscious of questions of power and intersectionality. Who is “local mob”? To whom are we listening and with whom are we building relationships? Are we conscious of attending to the voices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, LGBTQI+ folk, people with disabilities?

GREG: I’m interested to explore Indigenous approaches to theology – to deepen understanding of First Nations spirituality, culture, practice.

Indigenous theology

Deverell goes on to paint a picture of Indigenous theology … centred in:

The community of creation, rather than the reduction of community to the purely human.

The ancestral divinity of country, rather than the restriction of divinity to a Palestinian Jew and (in some traditions) his followers.

The ethics of caring for country, rather than a limiting of care to human beings alone.

The governance of people by Country (learning to imitate the patterns and processes of the non-human world), rather than the governance of everything by people.

The mission of Country together with human community, rather than the mission of Christians.

Rituals which celebrate and make present the ancestral divinity of Country, rather than a reduction of the divine to Christian symbols alone.

“If your theology is to ever leave the shores of the European enlightenment and come to live in this place, some radical transformations need to take place. And you need us to help you make those transformations.”

“[T]he churches are at a kairos, a threshold of decision: a critical or opportune moment … at a crossroads. You can either continue on the path you have taken since you arrived here – the colonising path, which is to make yourselves the centre of all things and therefore leading exploiters of both this land and its Indigenous people. Or you can take a different path – a path which would mean decentring yourselves, giving up a lot of that power and status to which you have become accustomed, and listening, instead, to the wisdom of Country and its children; listening to those whom you have habitually harmed and ignored …”

ANDREW: Are there First Nations preachers we could invite to bring the gospel? Are there ways other than the lighting of the Christ candle we might consider – liturgical symbols of divine light and presence, the “ancestral divinity of Country?” Are there First Nations people we could ask about this?

MIRIAM: I’m thinking about candle-making. Perhaps something for our Liturgy Resource group … creative use of colour, shape and decoration … A candle for use in Ordinary Time – rainbows, ochres, combinations of colours and shapes to symbolise the divine light? There might be First Nations people we could ask about this – or something similar …

Image: Aunty Lucy Waniwa Lester’s artwork The Last Supper. Supplied by Karina Lester and the Bible Society.

Image: Aunty Lucy Waniwa Lester’s artwork The Last Supper. Supplied by Karina Lester and the Bible Society.

August 2022: The Uniting Church in Australia and Uniting Aboriginal and Islander Christian Congress (UAICC) are mourning the passing of founding member of Congress and Anangu artist and interpreter Aunty Lucy Waniwa Lester.

UCA President the Rev. Sharon Hollis and Interim National Chair for UAICC the Rev. Mark Kickett have paid tribute to Aunty Lucy …

“Aunty Lucy had a significant and longstanding role in the life of the Uniting Church and UAICC. She attended one of the first Congress meetings on Elcho Island in 1983,” said the Rev. Kickett.

The Rev. Hollis added, “We pay tribute to Aunty Lucy for her leadership as one of the founding members of Congress and her faithful service to the Church and First Nations peoples over many years.”

Aunty Lucy Waniwa Lester was born at Tieyon station on Anangu country. The station was the northernmost homestead in South Australia, 1100km from Adelaide and 100km from the Indulkana settlement. Between bouts of work, Aunty Lucy and her family lived on the land, following the different seasons for game and bush tucker.

When she was about 8, Lucy moved to Pukatja (Ernabella Mission) so she could attend school. Ernabella was a Presbyterian mission station where First Nations people were encouraged to speak and retain their own languages. Lucy, who spoke Yankunytjatjara, was introduced to the Pitjantjatjara language. For many years in her life, Lucy served as an interpreter for speakers of both languages and even in her 70s was still volunteering as an interpreter in the Port Augusta prison, providing comfort to the many Anangu there.

Lucy later became a teacher assistant at Ernabella and studied early childhood education at what is now the Bachelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education (then known as Bachelor TAFE).

When she was 17, Lucy moved to Adelaide at the invitation of Dr Charles Duguid and his wife Phyllis where she lived with the family for many years. Dr Charles Duguid was the founder of Ernabella and the first lay moderator of the Presbyterian Church in South Australia.

Here she held various jobs with the Department of Aboriginal Affairs working in arts and crafts, and then at the Aboriginal Advancement League’s Wiltja Hostel at Millswood, which was established by the Duguids in 1956 to accommodate Aboriginal girls from country areas attending secondary schools in Adelaide. At the same time, Lucy volunteered at Adelaide hospitals, visiting and translating for patients from the APY Lands. It was through her hospital visits that Lucy met her husband Yankunytjatjara man Yami Lester who was being treated by eye surgeon in at the Royal Adelaide Hospital.

Yami born at Walyatjata (Wallatinna) in the north of South Australia. When he was 10, he was caught in a fallout cloud from the Maralinga nuclear tests, known by the local community as the Black Mist. Soon after he began losing his vision.

Yami and Lucy married in 1966 in the Grote Street Church of Christ. They had three children, Leroy, Rosemary and Karina. In 1970, Yami responded to a job to work with the Uniting Church in Alice Springs as an interpreter and this began a long ministry for Yami and Lucy in both the APY Lands and Alice Springs with the late Rev Jim Downing and the Institute for Aboriginal Development (IAD).

In 1981 Lucy and ex-President Dr Deidre Palmer were joint delegates at the World Federation of Methodist Women in Hawaii.

Lucy was also a great support to her daughters, Rose (now deceased) and Karina, in their fight against nuclear dump sites in South Australia.

Many others across the UCA and UAICC paid tribute to Aunty Lucy this week. Synod of South Australia Moderator Bronte Wilson celebrated Aunty Lucy’s work as an artist.

“Her artwork is an enduring reminder of her giftedness in expressing her faith and culture in meaningful ways,” he said.

UAICC SA Resource Officer and National Admin Assistant Ian Dempster paid tribute to Aunty Lucy as a role model, mentor and great encourager for emerging First Nation women leaders, particularly in developing their ministry and leadership skills.

“I first met Aunty Lucy in the mid 2000s when she was living at Port Augusta and was a member of both the Uniting Church and the Congress church. It was here she became a mentor for Aunty Denise, now the Rev. Dr Denise Champion,” recalled Ian.

“Some years later Aunty Lucy travelled with us to Putatja to an Anangu Women’s Camp at which Aunty Denise and Rev Helen Richmond were speaking. This was a precious time. It was great travelling with Aunty Lucy on the lands as she not only knew the languages, but everyone knew who she was.”

Ian also remembers the first time he saw Aunty Lucy’s artwork – a painting depicting the Last Supper in bush country. Lucy presented the work to the Rev. Ken Sumner at NCYC 2005 in Gawler. The artwork now hangs at Yarthu Apinthi, Uniting College, in Adelaide, and features in the Bible Society book of First People’s art, Our Mob, God’s Story.

“Lucy participated in the laying on of hands at Denise’s ordination and gave her a beautiful painting. More recently, Lucy gave a painting of a cross to Julia Lennon when she was commissioned as a Bush Chaplain, the first and only Aboriginal woman in this ministry with and through Frontier Services.”

Aunty Denise also recalled Aunty Lucy’s deep love of her heart languages.

“Lucy had a real love and passion for language, and her Yunkunytjatjara language. She always taught with deep wisdom and knowledge and used her language to do that.”

Paul Eckert, formerly of the Bible Society, said, “Aunty Lucy was always a great support for Bible translation work”. Currently the Old Testament is being translated into Pitjantjatjara.

Aunty Lucy is survived by her children Leroy and Karina and 11 grandchildren …

Material drawn from a story on Aunty Lucy in the newsletter of the Anglican Parish of Plympton as told to Harold Bates-Brownsword.

https://uniting.church/vale-aunty-lucy/.

Song

Midnight Oil, ‘Uluru Statement from the Heart’, The Makarrata Project, 2020. Read by First Nations collaborators: Pat Anderson, Stan Grant, Adam Goodes, Ursula Yovich and Troy Cassar-Daley.