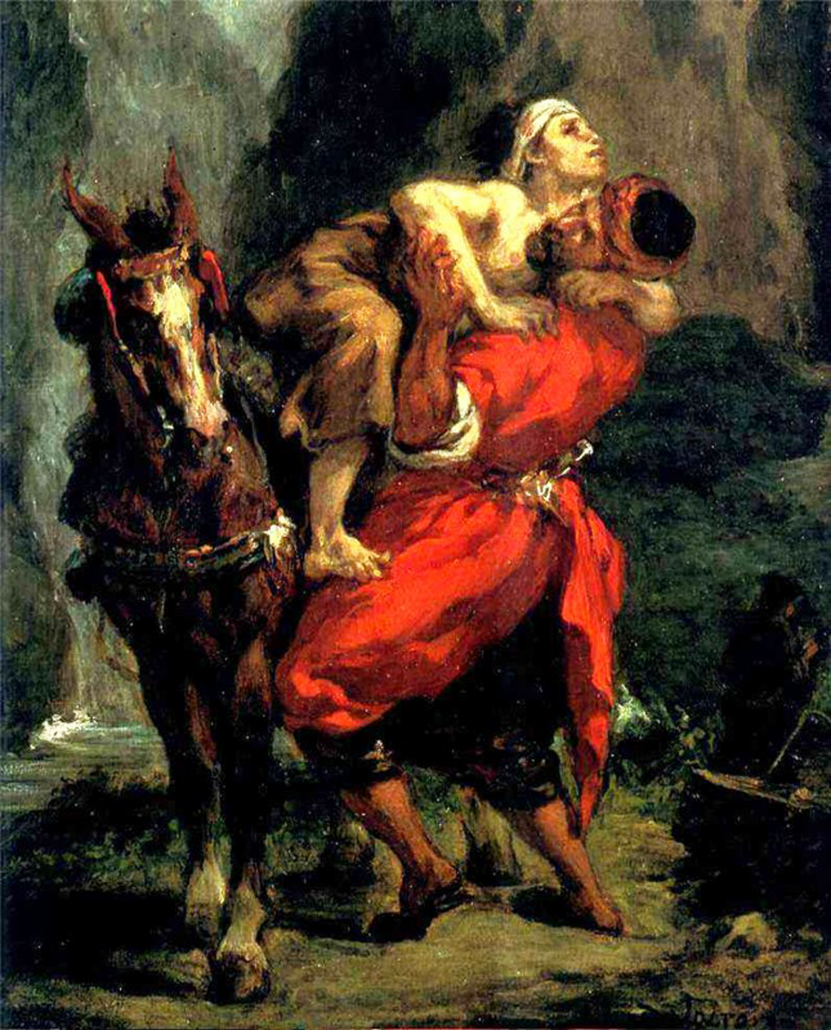

Image (detail): Vincent Van Gogh, ‘The Good Samaritan after Eugène Delacroix’, Oil on canvas 73 x 60cm. Saint-Rémy: May, 1890. Otterlo: Kröller-Müller Museum.

‘Go and do likewise’

Bible study prepared by Andrew

July 2022

Key text: Luke 10:25-37

Themes: Neighbour-love, compassion, action-reflection …

Readings

Exodus 29; Leviticus 19:18; Deuteronomy 6:4; Luke 1:5; Luke 17:11-19; John 4:4-26; Hebrews 10:19-23; 1 Timothy 2:5

Background

A Levite is a descendant from the tribe of Levi …

A priest is a Levite with special duties re worship in the temple …

Both priests and Levites were considered religious/pious. The priest was the more powerful figure …

The Samaritans claim descent from northern Israelite tribes who were not deported by the Neo-Assyrian Empire after the destruction of the Kingdom of Israel. They believe that Samaritanism is the true religion of the ancient Israelites, preserved by those who remained in the Land of Israel during the Babylonian captivity …

Some Christians, such as Augustine, have interpreted the parable allegorically, with the Samaritan representing Jesus Christ, who saves the sinful soul – the priest is the Law, the Levite is the prophets, and the Samaritan is Christ. The wounds are disobedience, the beast is the body of Christ, the inn, which accepts all who wish to enter, is the church … The manager of the inn is the head of the church, to whom its care has been entrusted …

Others, however, discount this allegory as unrelated to the parable’s original meaning and see the parable as exemplifying the ethics of Jesus.

The parable has inspired painting, sculpture, satire, poetry, photography and film. The phrase “Good Samaritan”, meaning someone who helps a stranger, derives from this parable, and many hospitals and charitable organisations are named after the Good Samaritan.

Artworks

Image: Vincent Van Gogh, ‘The Good Samaritan after Eugène Delacroix’, Oil on canvas 73 x 60cm. Saint-Rémy: May, 1890. Otterlo: Kröller-Müller Museum.

Image: Eugène Delacroix, ‘The Good Samaritan’, 1849. The man from Samaria puts the stranded traveller on his horse. Other passers-by had let the robbed man lay on the road – even though they were supposed to be more pious than the Samaritan. Delacroix here painted the figures as if he were Rubens: muscular and colourful. His own fast brushstroke can easily be recognised.

Further

“Within the Bible itself we see writers both respecting the past and transposing it to the present – or better, they respect the past by transposing it, thus allowing the past to continue speaking. Transposing the past is an act of wisdom …

“The Bible isn’t a book that reflects one point of view. It is a collection of books that records a conversation – even a debate – over time …

“Without the crisis of exile, the Bible as we know it wouldn’t exist …

“The questions for us, as they have been for all generations, are: What is our hope? How do we yearn for God to show up here and now? What urgent thing is happening right now to us, our families, and our world? What new thing will the God of old do now?

“[T]his process of reimagining God is not a problem to be overcome, but an invitation to meet the always active, always present God here and now, where we are, and to trust that God is with us in that process. By saying, ‘This is my God,’ I am accepting the responsibility of our inevitable task of finding those sacred places where God and our world meet …

(Peter Enns, How the Bible Actually Works, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 2019)

Peter Enns’ book celebrates the Bible as ancient, ambiguous and diverse (how wonderful!) – a resource for churches in pursuit of wisdom.

It seems apposite as we explore together, in and through a health and climate crisis, and a certain “exile”, wise means of caring and advocating for justice; wise ways amid fear and confusion; discerning a “sacred responsibility” as well as new opportunities …

Three aspects of religion (three approaches to reading)

- Poetics (What qualities of language or expression do we notice? Are there key words, phrases or images? What is the tone or feeling of the text?)

- Ethics (Whose calls for help, whose calls to justice do we perceive? How will we respond?)

- Metaphysics (Are we offered insights regarding the world? How might we describe or come to experience this world we live in?)

Read the following comments on Luke 10:25-37 and assign each to one or more of the “aspects”. What further questions are raised for you?

- “The people are the wounded man who’s bleeding to death on the highway. The religious people who are not impressed by the people’s problems are those two that were going to the temple to pray. The atheists who are revolutionaries are the good Samaritan of the parable, the good companion, the good comrade” (Laureano, The Gospel in Solentiname).

- “The fact is that in your neighbour there’s God. It’s not that love of God gets left out, it’s that those who love their neighbour are right there loving God” (Elvis, The Gospel in Solentiname).

- “The man fallen by the wayside in Jerusalem, he was the temple” (Ernesto Cardenal, The Gospel in Solentiname).

- “The hostility between Jews and Samaritans at the time makes the phrase [good Samaritan] an oxymoron – as phrases like ‘good terrorist’ or ‘good drug dealer’ would be for us” (Brendan Byrne).

- “The concept of ‘neighbour’ shifts from being a tag that I may or may not apply to another, to being a quality or a vocation that I take upon myself and actively live out” (Brendan Byrne).

- “The Samaritan was not behaving like a neighbor in incurring unlimited liability for the expenses and needs of the wounded person; he was behaving like a lover” (Sally Purvis).

- “The attention to the corporeal, which the Samaritan enacts for the wounded stranger and which a woman enacted for Jesus (7:36-38), signifies an eros of divine visitation. But in the episode which follows (10:38-42) the eros of divine visitation is displaced in a narratorial splitting between hearing and doing which signifies a division between women” (Anne Elvey).

- “Like the servants in the parable of the prodigal son, the domesticated animal, pet, or pack-animal in the parable of the good Samaritan is backgrounded. Other than to note parallels with other biblical texts or to signify the status of the Samaritan – as one who has the means to ‘possess’ such an animal – the presence of the animal in the narrative goes largely unremarked” (Anne Elvey).

- “It is not that the animal is outside the story, rather that it is part of the assumed inside. Nor is it that the text would preclude a response from the animal. Indeed, in bearing the other, the animal does precisely what is necessary. As later a similar animal bears Jesus toward Jerusalem (19:28-40), Jesus claims that even stones might respond to the divine visitation (19:40)” (Anne Elvey).

- “Non-human nature as independently responsive to the divine is forgotten in the text or where remembered it is as a violent homogenisation which is counter to the plural otherness of Earth (3:4-5)” (Anne Elvey).

- “If there is to be an ecological bearing of the other, a passionate compassion must first submit to the prior claim that humanity is borne by Earth and Earth others, just as the wounded person was borne mutually by the backgrounded pack-animal and the Samaritan” (Anne Elvey).

- “Eternal life has to do with negotiating a steep path, inhabiting a liminal space where dangers abound, but also opportunities – to cultivate compassion, to collaborate with human and Earth others; to recognise need, to affirm goodness” (Andrew Collis).

- “There is a religion that is propaganda, a religion that is sentimental and self-serving, and there is a religion that calls us to move beyond our comfort zone to the space of otherness” (M.P. Hederman).

- “The gospel teaches care for neighbours – practical and sensuous. Attentive, sensitive – a lover’s care calls to mind the extravagance of a woman who pours out precious ointment (soothing, fragrant) upon the body of One maligned and marked for death (Luke 7:36-50 and quasi-parallels). The gospel teaches care for neighbours – personal, communal, cross-cultural. A passionate compassion (Anne Elvey) calls to mind the Samaritan woman at the well (John 4:4-26). When Jesus needs a neighbour (he is tired and thirsty), she is there … offering spiritual intelligence – playful, philosophical, astutely political – sharing his concern for reconciliation and for true worship (that is, non-idolatrous love)” (Andrew Collis).

- “‘Go and do the same,’ says Jesus. And we are drawn (again) to a place where neighbours feel and befriend, touch and tend, find their way and follow through … where neighbours and neighbourhoods are transfigured … ‘Go and do the same’ means don’t resist, don’t miss out, join in” (Andrew Collis).

ABNER: There are risks involved whenever we choose to help someone – discerning when and how to help – how many people to involve in the process.

CATHERINE: The key moment in the parable is the moment when the Samaritan is moved to compassion. He works out what to do from there.

NORRIE: The horse plays an important part, and the innkeeper too. Neighbour-love is about the whole community – finding help and support wherever it is needed, and affirming that.

Songs

Sydney Carter, “When I Needed a Neighbour”, 1965.

The gospel and the song express something fundamental. Faith is a fundamental disposition, openness to the other – receptivity, mercy, kindness … love. It’s striking that neighbourly love shapes/informs whatever it means to love God (the “religious” figures in the parable fail to appreciate and act on this). God, we might say – and Christ the icon – is the neighbour.

Moreover, in love we become Christlike, we become neighbours – comrades, friends – in space and time. Neighbourliness defines our spirituality, our concern for the next person, our concern for the next generation.

When Jesus needed a neighbour (he was tired and thirsty), a Samaritan woman met him at Jacob’s well in Palestine (the site remains of holy significance for Jews, Samaritans, Christians and Muslims). An older gospel song tells this story from John 4.

The woman, according to Orthodox tradition, Photina, is someone with whom Jesus can talk. In a fashion deemed scandalous by patriarchal custom, they talk (publicly) about water and life, true love and worship (the most important things).

There’s a connection, an understanding, mutual affection and trust. Their conversation is layered – not simply about personal wants and individual choices but social, political …

St Augustine, among others, sees that Jacob’s well (Jacob and Rachel’s well) hints at a deeper nuptial reading of Jesus as the Bridegroom of Israel (and therefore the Church) come to reunite the divided tribes.

Photina (the “Enlightened One”) engages Jesus wholly. It’s no surprise to read, then, that she becomes a bearer of good news – an evangelist in the name of reconciliation and peace.

Bob Dylan, “Desolation Row”, 1965.

“And the Good Samaritan, he’s dressing, he’s getting ready for the show / He’s going to the carnival tonight on Desolation Row …”