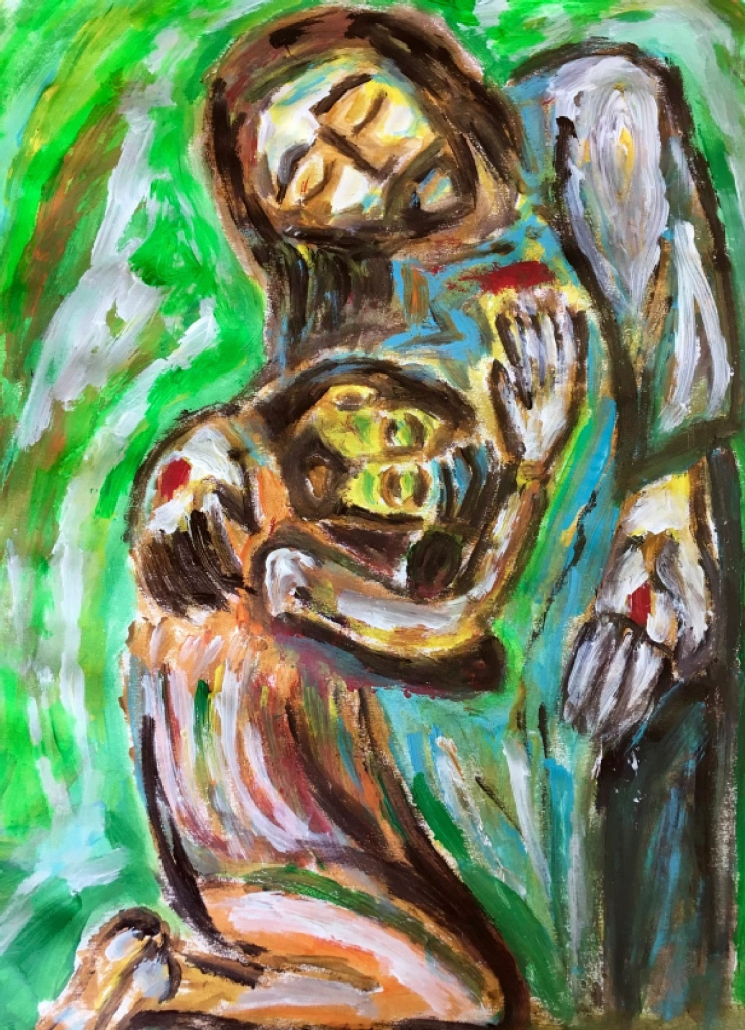

Image: Orthodox Icon of Saint Thomas (detail).

‘In (and out of) touch with flesh’

Bible study prepared by Andrew

April 2023.

Thursday April 13, 7-8.30pm.

All welcome. At the manse or via Zoom.

Join Zoom Meeting

Meeting ID: 858 1336 0721

Passcode: 032351

Reading: John 20:19-31

Key texts: John 10:10; 11:16; 14:5; Luke 10:30ff.

Themes: Faith and doubt, wounds of Christ and the wounded body of Christ, incarnation and excarnation.

1.

Our gospel invites us to consider doubts and deep questions – our struggles to believe in Jesus as the embodiment of God’s love. It’s not really such a controversial topic. Of course, doubt and faith work together. There is no pure faith devoid of questions or the need of discernment. We should be wary of any such “faith”. Likewise, a persistent disbelief or cynicism is tedious – closed-minded, closed-hearted. “Don’t persist in your unbelief,” says Jesus, “but believe!” (v. 27).

It is one of the fourth gospel’s delightful paradoxes that its climactic statement of faith should be drawn out of doubt/disbelief and, if we recall earlier statements of Thomas, a pronounced tendency to the negative (11:16; 14:5). Thomas the Twin says/prays: “My Saviour and my God!”

So, we can consider doubt in concert with faith. Coming-to-believe as a matter of sense and sensitivity, interpretation, “paschal testimonies”, again and again. “In concert” entails practice and performance, engagement with tradition, at a certain place and time. “In concert” also means with others (as illustrated by Thomas reuniting with the other disciples).

Metaphysical doubts, I think, are among the least interesting. Speculation as to the nature of a risen body, as to the moment or magic of resurrection/ascension. These are literal-minded questions in which to get stuck. The fourth gospel calls such speculation an insistence on signs, a demand for miracle as magic. In contrast, Jesus invites us to consider the meaning or Spirit of the sign.

A Spirit of grace, defying the limits of space and time, life and death. A Spirit of bodily existence, bodily resurrection. A Spirit who raises Jesus of Nazareth (a crucified Christ) to new life – the One who unites scattered disciples, the One who empowers frightened/despondent believers.

And there are deeper questions, more pertinent doubts.

Is there really a “divine” power in non-retaliation? Power in forgiveness? Power in peace?

Is there a good reason to give my all – to someone, to a cause or project, to my God?

Is there value in trying, again and again? What if the fruits of my efforts wither and fall?

Doubts about my capacity to discern goodness in myself and in others … our collective sense of what’s right, fair, beautiful …

Doubts about trust, motivation, inspiration …

Doubts about emotional maturity …

Doubts about my ability to learn, grow, heal, recover, love, grieve, think, make, communicate, pray, listen, look, touch, hold, nurture, remember, wait, promise, keep a promise, read, run, plan, stop, rest, start again …

Doubts about humanity’s “light”, wisdom, resolve …

What to do with these doubts?

Express them? Resist them? Repress them? Obsess about them? Live with them? How? Allow them, in their own ways, to lead us into faith?

The gospel teaches that Jesus comes to us in our fears and responds to our doubts that we might have the faith to take the next step.

Then Jesus says: “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.”

The beatitude asserts that believers of later generations are in no less advantageous a position than the original witnesses. “There is even a hint of a greater blessedness accruing to [us] because a deeper, more creative faith is going to be drawn from [our] hearts” (Brendan Byrne).

In what ways are you led by doubts and questions into faith?

ABNER: I think about respectful and disrespectful or abusive touch. What is the difference?

ANDREW: Aristotle, who regarded touch the primary sense, might say that respectful touch entails a double sensation – we touch and are touched in return – whereas disrespectful touch fails to acknowledge the presence and desire of another.

ABNER: Disrespectful touch is grasping, taking … violent and greedy …

…

2.

What kind of touch is desired by Thomas and by Jesus? The initial words of Thomas might be regarded insensitive: “I’ll never believe it without putting my finger in the nail marks …” When he later exclaims “My Saviour and my God!” it is not clear whether he has touched the hands or side of the Wounded Healer.

I imagine the quivering finger of Thomas moving toward the wounds, hovering, suspended between unbelief and belief, between faithlessness and faith. Wounds and marks of violence, marks of abuse, pain and hurt call for respect, for gentleness, for reverence.

If ever we touch a wound or scar of another, we take all manner of precautions, in the name of cleanliness, clinical or pastoral care. Perhaps we touch with the touch of our eyes only, or by means of a swab and solution or balm of some kind.

Fr Ronald Raab painted this artwork (below) with a cloth, depicting a tiny space between the fingers of Thomas and the wound of Jesus. An intimate space. As though the Spirit herself conducted the healing. As though the Spirit herself conducted believing.

The artist, ordained 34 years, says: “My entire priesthood has been about tending the wounded body of Christ by listening to and being with people who long for God, those who survive on the margins of society.”

The gospel invites not grasping Jesus’ identity as such, but embodying the healing vision of Jesus, whose touch was a gesture of valuing those who were devalued, giving integrity to flesh and recognising the ways in which certain persons are marked as outsiders.

Our friend Anna Jahjah directed a play about Frida Kahlo (Viva la Vida). The Mexican artist painted her own reality (see below, ‘Two Fridas’, 1939), which included significant pain and suffering. Unimpressed by contemporary avant-garde male artists, and betrayed by an insensitive and ambitious husband, she painted/presented herself – a fiercely intelligent/feminist and politically engaged woman with a disability – in ways that others found and continue to find (increasingly so) empowering.

We gather around the image of the risen Jesus – encouraged to attend to wounds rather than to cover over or erase them. We are invited to carry forward the message of Jesus by telling truths about the wounds we bear in life. Respectful/godly love has the capacity to touch shame, grief and anger, and healing encounters underscore the revelation that resurrection is already taking place in the midst of things.

“[Jesus] bears witness in his body to the flesh of the world, marked in multiple configurations … When Thomas gazes at this body, he is drawn into the fabric of flesh reconstituting” (Shelly Rambo, Resurrecting Wounds, 2017).

Let us tell the truth – to our God at least and to God at first – about the wounds we bear. As individuals in relationship, in community and in history … I am wounded by guilt, failure, disappointment, anxiety, greed, vanity … I am drawn into the resurrection …

ALISON: I am reading a book about cancel culture. Attending to wounds, to woundedness, means resisting cancel culture – we will not cancel each other. There can be other ways to address differences, even hurts … in the interests of transformative justice. We are responsible for each other’s transformation … wholeness.

JANE: I am reminded of the parable of the Good Samaritan who tends the wounds of a stranger – washes, dresses and cares for a stranger …

JOHN: Respectful touch includes washing – even washing the body of a deceased person.

ANDREW: Baptism is about dying and washing, too – incorporation into a community of care, reverence for life … for life after death … where the dead are washed and cared for …

ALISON: Yes, dying with Christ who cared for the fallen and the dead, who trampled the gates of hell and so on … dying and rising with Christ.

…

3.

Orthodox icons of Saint Thomas depict him as a beardless youth (young at heart, bold, adventurous). Sometimes he holds in his hands his great confession of Christ as “Saviour and God”. The Slavonic inscription reads, “The Belief of Thomas”.

According to philosopher Richard Kearney, Thomas was also a healer-educator of Jesus. He was the disciple who helped his master resist the erasure of scars in a Glorious Body that is no body at all. He refused the lure of excarnation.

The risen Jesus heeds Thomas’s challenge in the Upper Room to remain true to his wounds, to keep his promise of ongoing incarnation as a recurring Christ who returns again and again, every time a stranger gives or receives food …

This repetition of Christ as infinitely returning stranger – in the reversible guise of host/guest – is what Kearney calls anacarnation (from the Greek prefix ana- meaning “again”, “anew” in time and space). It is a story of endless carnal reanimation, captured in the verse of Gerard Manley Hopkins: “… Christ plays in ten thousand places,/ Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his …”

Anacarnation is the multiple repeat-act of incarnation in history. Resurrecting not only in the future after Christ but also in the past before Christ, through countless identifications with wounded strangers, forgotten or remembered. It signals the tangible reiteration of Christ, bringing Jesus back to earth in a continuous community of solidarity and compassion. “Your kindom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.”

And by this reading, Thomas ceases to be a “servant” and becomes a “friend”, even “mentor”, of Jesus – a doctor-teacher who holds Jesus to his word made flesh, ensuring he remains faithful to his carnality.

Thomas, hailed as patron saint of medicine in India, has no time for supersensible erasure or one-way ascension into heaven. In short, Thomas acts in keeping with the Samaritan woman at the well and the Syro-Phoenician woman at the table – all outsiders from the margins, teachers from the basement, reminding Jesus that his divinity is in his tangible humanity, that the right place for the infinite is in-the-finite.

Otherwise, Christian in-carnation becomes ex-carnation, a fundamental betrayal of Word made flesh. Thomas will have none of it: he climbs to the Upper Room to bring Jesus back to earth.

In Christ, as the first letter of John tells us, God became a person “that we can touch with our hands”. To forget this is to forget the message: “I come to bring life and bring it more abundantly” (John 10:10).

The history of Christianity is a story of being in and out of touch with flesh. It is out of touch when it betrays the truth of Word-made-flesh, veering toward notions of anti-carnal gnosticism and puritanism. Witch-hunting and the inquisitorial persecution of “pagan” earth religions and sensuality were symptoms of such puritanical zeal.

The resultant pathologies of sexual repression and abuse, misogyny and repudiation of bodily joy tell their own story. But it is only half the story …

The good news and power of God has to do with healing touch.

As we continue to emerge from isolation and apprehension …

As we embrace our opportunities for ministry and community partnership …

As we practise and refine the art of healing touch – vulnerability, sensitivity, tact …

As we allow the world around us to touch and move and change us …

Praised be holy intimacy, holy friendship, creaturely companionship.

See Richard Kearney, Touch: Recovering Our Most Vital Sense, CUP, New York, 2021.

JOHN: I had a dream about Jesus. He appeared to me in a dream, glowing bright like the moon. He said to me, “Do the right things” – in such a lovely tone of voice. I felt something.

ALISON: This kind of touch undoes us … like in dreams or memories of loved ones. When my mother passed, sometime after she passed, I was handling some of her clothes – then I sat inside the closet and cried.

…

Song

Willie Nelson, ‘Angel Flying Too Close to the Ground’ (Live at Budokan, Tokyo 23/2/1984). A beautiful song about freedom and healing – note Willie’s fine touch as a singer and guitarist, his beloved and “wounded” guitar, Trigger.