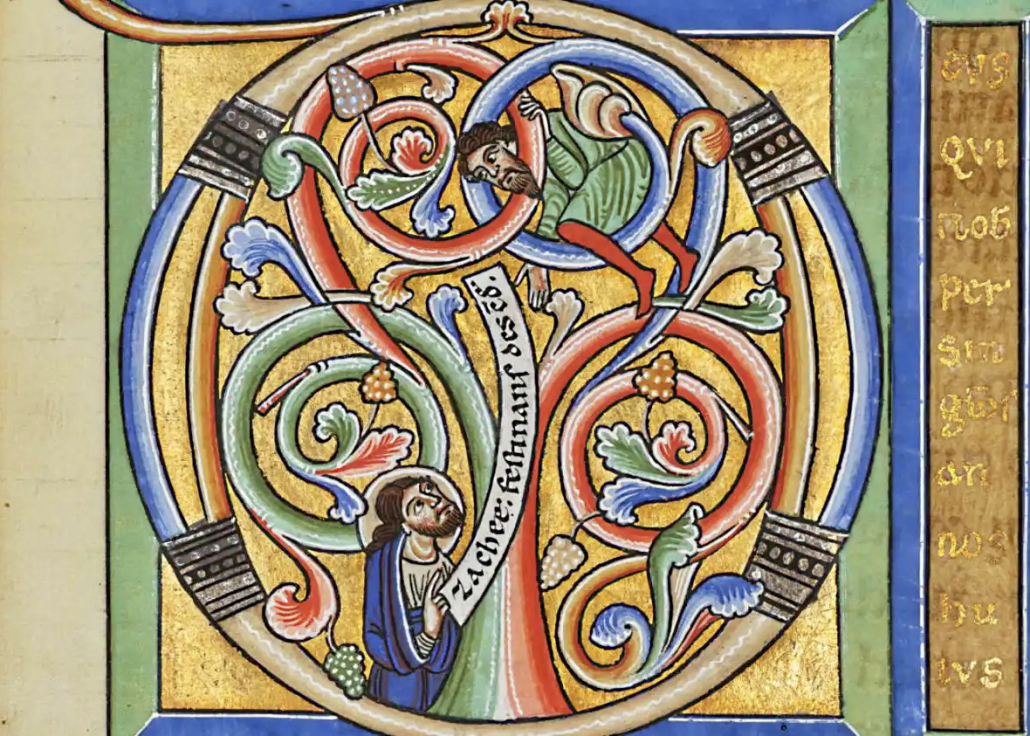

Image: Illustration taken from a 12th century German illuminated text.

‘A force greater than self-importance’

Andrew Collis

Ordinary Sunday 31, Year C

Wisdom 11:22-12:2; Luke 19:1-10

“You love everything that exists / And you don’t hate anything you have created … / You save all things because they are yours …”

Words from the book of Wisdom, a book, as protestants, we don’t often open and read – a book we call apocryphal, or hidden away, amid texts of uncertain authenticity in the eyes of 16th-century reformers.

And yet, texts making something of a comeback in ecumenical, postmodern and feminist, new materialist circles – Wisdom reclaimed as the feminine figure of divine life animating all that is good in the world, in human histories and cultures.

We might say, both affirming and overturning the apocryphal status of such texts, that Wisdom is indeed hidden away – we might say, as did the apostle Paul, that Wisdom is hidden away in the very life of Christ – in the manger, upon the cross, within a small group of believers in a Christ crucified – in a small group of resisters, pacifists, dreamers, evangelists, egalitarian/communitarian poets, prophets and martyrs in various corners of empire.

A personal interest in Wisdom/Sophia leads to a little-known tradition in Jewish folklore, dating to the Babylonian Talmud (the first half of the third century BCE).

The traditional story is this: The entire world rests on the merits of 36 anonymous righteous persons living in each generation. These hidden saints, called in Yiddish, lamed vov-niks, go unnoticed by others due to their self-effacing, humble nature. In times of peril, however, the lamed vov-niks make a dramatic appearance, using reserves of faith and strength. The number 36, renowned in the Midrash, kabbalah and folkloric legends, is symbolic. It is twice the number 18, or chai, meaning “life”.

In a time of peril – oppressive patriarchy, imperialism, environmental catastrophe – 36 hidden saints make a dramatic appearance in the name of life, and for life’s sake.

What do we make of such a story? Is it a hopeful story for us?

Would you dare hope for 36 righteous persons in our world right now (about the number of SSH volunteer contributors; the number of SSH volunteer distributors; the number of people attending an opening at the Orchard Gallery; or involved as community gardeners?; or here on a Sunday morning)? How might such persons, hidden saints, reveal themselves? What might they say or do?

And what has this to do with the gospel?

Our gospel for today is the story of a person called Zacchaeus, a maligned and marginalised person in Luke’s gospel. Zacchaeus is a tax collector and so a Roman sympathiser and enemy of his own people.

Zacchaeus, moreover, is a chief tax collector and so a very wealthy person and very much on the outer when it comes to the reign of God – Luke’s Jesus has been quite clear: “…woe to you rich” (6:24); “You can’t be my disciple if you don’t say goodbye to all of your possessions” (14:33); “You can’t worship both God and Money” (16:13c); “The rich person said, ‘I beg you, then, to send Lazarus to my own house where I have five siblings. Let Lazarus be a warning to them, so that they may not end in this place of torment” (16:27-28).

I’m not sure whether there’s a Hebrew number for death, but Zacchaeus would symbolise twice the number – he is doubly dead.

And yet, this may be one of the most subversive texts of Luke’s gospel, for the name Zacchaeus means “innocent or righteous one”. Could this wealthy Roman sympathiser be a righteous one? A hidden saint? One of the 36 lamed vov-niks?

Is righteousness, is Wisdom, so thoroughly hidden away – even within Luke’s gospel? If so, might we not be called to reconsider, at every turn, our judgement on the one we regard beyond the reign of God? The one (without or within) for whom we make no room at the table? The one (without or within) to whom we secretly refer when we pray: “I give you thanks, O God, that I’m not like her/him/them” (18:11b).

Does the gospel, at every turn, elude us … irreducible to ideology, bigger than our best politics?

What if there were a person we regarded doubly dead, beyond righteousness, a person at the very door of life – even having climbed a tree of life? How might such a person, such a hidden saint, be recognised?

Zacchaeus is short. He is short on innocence and righteousness. He is crowded out, pushed aside. And yet, whatever it is in him that wants to see Jesus is willing to appear foolish.

A wealthy enemy of the people, then as now, is not given to climbing trees, let alone seeking, in full view of the crowd, a poor preacher-healer from out of town.

“Even though he was an important guy, he shinnied up a trunk like a kid; he didn’t mind looking silly. He didn’t look like a rich man up there, just like a youngster that’s going to see something that interests him” (Tomas Peña, The Gospel in Solentiname).

The dramatic appearance of this hidden saint, then, is marked by a willingness to appear weak. A force greater than self-importance is at work in him. That’s how this saint appears – in a way, it would seem, surprising even to himself.

And Jesus is quick to discern it – to discern the vulnerable person, the person. “Zacchaeus, hurry up and come on down. I’m going to stay at your house today.”

Jesus, in other words, joins Zacchaeus in willing to appear foolish. Their mutual welcome is an offence to others present.

Can we imagine it? Jesus and Zacchaeus discussing the dinner menu? Laughing? A force greater than self-importance is at work in them. Grace, we say, makes for transformation – by way of tears, laughter … the overcoming or undermining of identity as projection, as project. The beginning of identity as gift, a new self in relationship.

Not to be naïve about this. But not to be blind to the vulnerable, the good and the human, either. Not to be so confident in our political or ideological wisdom that we miss the revelations of Sophia right before our eyes.

Luke goes on to tell us that Zacchaeus, made safe in his vulnerability, given opportunity to welcome the God who comes “to search out and save what [is] lost”, is a new person. He won’t go on oppressing others. He begins to make amends – to rebuild relationships of trust.

That’s the meaning of salvation, Luke tells us. It comes by way of a vulnerable human heart. It comes to a house, to a place of welcome. And it comes to extend a story whose origins lie with Sarah and Abraham – in other words, it comes to extend a community whose origins lie in vulnerable trust and hope in God’s future.

The story of Zacchaeus is one story of salvation. There are, at any given time and place, another 35 – another 35 at least. Amen.