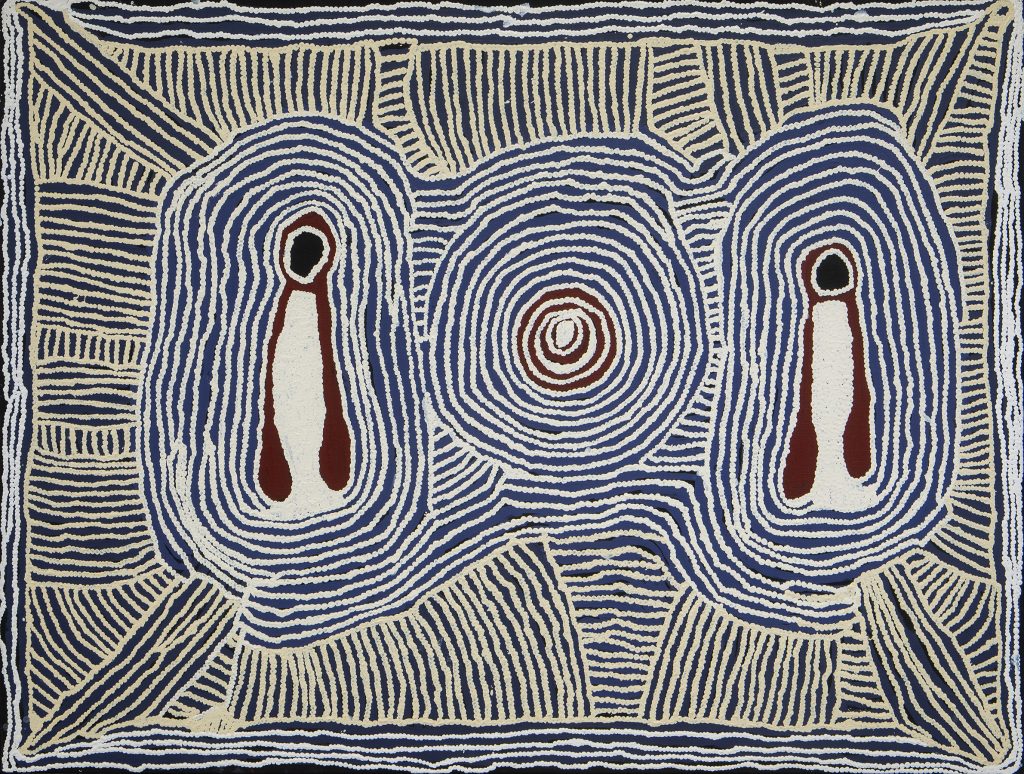

Image: Linda Syddick Napaltjarri (Pintupi, ca. 1937-2021), ‘Nativity’, 2003.

Linda Syddick (Aboriginal name Tjunkiya Wukula Napaltjarri) (ca. 1937-2021) was a Pintupi artist from Australia’s Western Desert region whose work was influenced by her Christian and Indigenous beliefs and heritage. Living a seminomadic lifestyle until the age of 8 or 9, she settled with her family at the Lutheran Mission at Haasts Bluff in the 1940s. She was taught to paint in the 1980s by her uncles Uta Uta Tjangala and Nosepeg Tjupurrula, who were both significant figures in the Papunya Tula art movement. She painted Tingari and biblical stories and was a three-time finalist for the prestigious Blake Prize. Her works are held by the National Gallery of Australia, the Art Gallery of NSW, the Art Gallery of South Australia, and many other institutions.

In Syddick’s ‘Nativity’, a series of wavy, concentric blue and white lines encompass Joseph, baby Jesus, and Mary, while many more lines in blue and beige converge on the trio from the image’s border. The artwork conveys a vibrating joy! And myriad pathways leading to the birth of the Saviour. Jesus is the centrepiece of the composition, a little tot represented geometrically as a circle. A sun? An egg? A pebble thrown into a lake, sending ripples outward? A reverberant well?

‘Heavenly folk songs’

Andrew Collis

Christmas Day, Year C

Isaiah 9:2-7; Psalm 96; Titus 3:4-7; John 1:1-14

“I know that I can sing, that I can write. But what I’m really good at is understanding what a lyric is about. I always ask questions about the context of the lyric, enter into it, become the lyric … [and] I became a better singer as I gained more life experience …” (Agnetha Fältskog, 2013).

Agnetha Fältskog is the soprano voice of ABBA pop classics including “SOS”, “Knowing Me, Knowing You” and “The Winner Takes It All”. There’s a certain melancholic wisdom she brings to the drama of a song.

I think on this not just because our gospel theme has to do with the Word (of love) made flesh, but because Christmas carols, heavenly folk songs, invite us to sing – to become better singers in some way. To bring our life experiences to the task. How might we sing this one? How might we relate to it? Inhabit it?

A lyric is not just words. A song is a dwelling place. By imagination, we enter into a mode of being where words, rhythm and melody shape perception and identity.

A lyric is not just words. When we sing a lyric, we dwell in a flow of moments where past, present and future interweave.

A lyric is not just words. Inhabiting a song blurs the line between self and other. Who is speaking? Who is feeling? The lyric becomes an extension of the singing self or group – our voices carry its meaning and yet it remains something other.

A lyric is not just words. A song is an embodied event. It is felt, not just thought.

A lyric is not just words. When the lyric ends, the silence that follows resonates. The lyric lingers. The silence afterward asks: What remains within us of the song?

I wonder about the song “Silent Night”.

The world’s most recorded Christmas carol was first performed on Christmas Eve, 1818, at the Nikolauskirche, the parish church of Oberndorf, a village in the Austrian Empire on the Salzach river in present-day Austria. A young Catholic priest, Father Joseph Mohr, had come to Oberndorf the year before. In the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, he had written the poem “Stille Nacht” in 1816 at Mariapfarr, the hometown of his father in the Salzburg Lungau region, where Joseph had worked as an assistant priest.

At least as famous as the story of the carol’s origin is that of its role in the Christmas truce of 1914. In his book on the truce, historian Stanley Weintraub identifies the singer as Walter Kirchhoff, a German officer and sometime member of the Berlin Opera. Kirchhoff’s singing of the carol in both German and English is credited with encouraging the exchange of songs, greetings and gifts between opposing soldiers.

Whose world do we enter? Which Christmas? A time of childhood or adulthood, war or peace? “All is calm, all is bright …”

There’s the world of Luke’s imagination: Bethlehem, “House of Bread” … city of Naomi, Ruth and Boaz, city of David … city in Judea …

There’s the world we might care about: Bethlehem in the Holy Land, in the West Bank, occupied by Israel since 1967. What do we see? What do we anticipate happening there? For all God’s people. “Holy infant, so tender and mild …”

Who resists our interpretation? What eludes us? There’s something strangely transcendent. “Shepherds quake … Glories stream …”

Like the blue, white and beige lines of the artwork by Linda Syddick Napaltjarri … “Nativity” (2003) … myriad pathways leading to the birth of the Saviour …

Wiradjuri poet Jazz Money wonders: “Can we dream up the world we want for our next ones? Can we sing it together?

“The future I want for my babies is one with sovereignty held by First Nations peoples across the world, self-determined and determined by care. A future with the climate crisis reversed, the bush in bloom. A world that will not demand gender or sexuality, not be shaped by capitalism and imperialism. A time not so far away.”

How does the song make us feel? Sad? Worried? Alive? Joyful? “With the dawn of redeeming grace …”

And what imprint or trace does the song leave behind? With what, with whom are we left? “Silent night! … love’s pure light …”

To inhabit a song lyric is to be suspended between self and other (us and not-us), time and eternity, sound and silence. It is an act of interpretation and participation – a temporary dwelling in which language becomes lived; in which we become subjects and witnesses.

All this, at least this. As the psalmist says: Every day calls for a new song of gratefulness to God. “Christ the Saviour is born!” Amen.