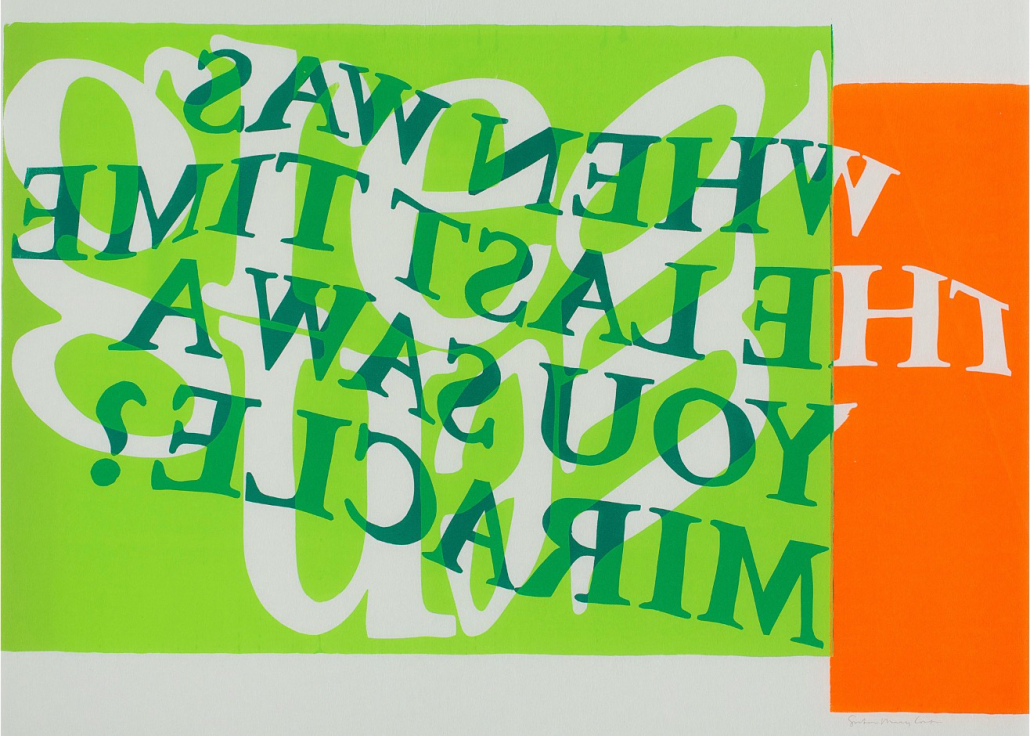

Image: Corita Kent, ‘green up’, serigraph, 1966.

‘Lifting up and bringing down – love on the level’

Andrew Collis

Epiphany 6, Year C

Jeremiah 17:5-10; Psalm 1; Luke 6:12-26

“It is the vulnerable who make the world safe for humanity,” says biblical scholar Brendan Byrne in conclusion to a three-page commentary on today’s gospel. Byrne’s refrain repeats with a difference the words of Jesus: “You who are poor are blessed, for the reign of God is yours.”

Jesus is teaching the 12 apostles in close proximity to a wider group of disciples, within earshot of the crowds from Judea, Jerusalem, Tyre and Sidon – the afflicted masses who have come to hear Jesus and be healed of their diseases.

This is Jesus whose own vulnerability is underlined in his birth in a manger, his yearning/learning as a youth, his temptation in the wilderness, the hostile response to his first-time preaching in Nazareth, and, in today’s text, an ominous reference to Judas Iscariot (v.16).

Most commentaries point out that “blessed” means something like “happy” and that the Beatitudes, the Blessings, are a series of provocations, the sharpness of which centuries of familiarity have tended to soften.

Jesus knows that what he is saying is absurd by standards of his day. His words – like Sister Corita’s artwork – deal in radical reversal. A world of winners and losers is turned upside down by way of hope and courage, by way of subversive wisdom.

The blessings and woes introduce a sermon on the cost of discipleship.

Jesus will go on to speak about loving enemies, sharing possessions, loving the unlovable (unconditional or non-preferential love), being non-judgemental and forgiving, living by the “golden rule” – leaving the conventional, the familiar, to bear a cross, to confront oppressive powers … and follow him (imitate, appropriate, repeat with a difference his loving example).

Similarly, Corita Kent’s artwork invites us to imagine the world, to see ourselves, as if from the “other side” (the heavenly side?) of reality. As if from the “underside” of history – an all-too-human, exploitative, heteronormative colonialism.

We read: “When was the last time you saw a miracle?” And, with greater difficulty, the text reversed out of light green, upside-down and sideways: “Green up.”)

This is a demanding vulnerability.

It places a disciple alongside the one made poor: alongside the economically and socially poor, alongside the faithful who wait upon God (those like Simeon and Anna), alongside all those (right there in the crowds) with a deep longing that makes them vulnerable to need and despair, ridicule and abuse.

“[A]ll whose emptiness and destitution provide scope for the generosity of God.”

Mary proclaimed it in her song. It is also the “good news for the poor” announced by Jesus – with reference to prophetic acts of indiscriminate love.

God is this love on behalf of the oppressed. That’s why it’s better to be poor, hungry, weeping and reviled rather than rich, full, laughing and well-spoken-of. Because God takes sides and will reverse the situation.

Being vulnerable, then, gives scope to divine power – to lift up, to bring down, to make well. A vulnerable community (long-suffering and persecuted, and including those like Levi and Zacchaeus, wealthy tax-collectors become generous benefactors) can become an instrument of the hospitality of God.

It is the vulnerable who make the world safe for humanity … because it is the vulnerable through whom God acts.

When will God do this?

One answer is that God has already done this in Christ. God has made the world safe for sinners/oppressors by forgiving them (forgiving but not excusing them/us). God has made the world safe for the oppressed/afflicted by accompanying them, by healing and loving them, weeping and hoping with them. God has established a church as counter-cultural community of shared resources, shared suffering and glory.

A fuller answer is that God continues to do this – at any moment God might do it again – by the insistent power of the Spirit. We are invited – called, provoked, nudged – into a sacred realm or reign – to be witnesses to the safety of God we ourselves may embody – in a community where justice, equality and compassion are new realities.

How do we do this?

Voluntary poverty of one kind or another has long been a way of closeness to God, as has radical service of one kind or another. The common thread is living with less so that all might have enough, rejecting an anxious pursuit of wealth, power and security, allowing God (through sacred text and sacrament) to inspire generosity and care.

It is the vulnerable – strangers/outsiders with gifts of hope, courage and wisdom – who make the world safe for humanity.

Let us note in closing the image in verse 19 of Jesus from whom a healing power streams. It is, perhaps, the very power of the sermon itself: calling, provoking, nudging, inspiring …

It is blessed to be vulnerable – there is joy in it – for there one meets with strangers/outsiders – all of us afflicted and needy (as if in a mirror, as if on the other side, the underside or heavenly side).

There, with open hands (empty, not grasping), we receive our new and truer selves – as in bread and wine. May it be so. Amen.