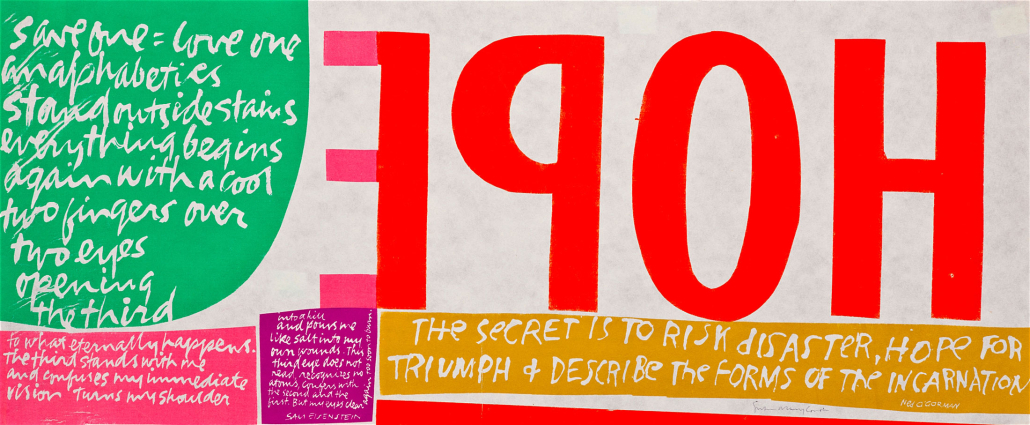

Image: Corita Kent, ‘hope’, serigraph, 1968.

‘Not just any dream will do’

Andrew Collis

Epiphany 7, Year C

Genesis 45:3-11,15; Psalm 37; Luke 6:27-38

Two dreams: the dream of reconciliation; the dream of peace (non-violence, love). Desmond Tutu refers to the reign of God as “God’s dream”.

“I am Joseph,” says the teary dreamer whose story is all about dreams, covenant promises coming to fruition. “I am Joseph,” says the dreamer to those responsible for his suffering. “I am Joseph … I mean you no harm … I desire your happiness, your wellness.”

“Love your enemies,” says the teacher-dreamer whose life, death and resurrection centre about God’s dream. “Love your enemies,” says the dreamer to would-be followers and peacemakers. Use your imagination … do good to those who hate you; bless those who curse you; pray for those who abuse you.

Joseph and Jesus speak boldly. They also risk bold action. The invitation is for us to take our own risks.

Regarding family and political violence – both within view – the texts are illustrative and not prescriptive, yet no less compelling for that. The dream is the call. The dream calls us to “make love happen”, to make the impossible possible, to embody the divine.

Joseph and Jesus speak and act with reference to a God of compassion, with reference to abundance and forgiveness (Joseph artfully discerns the hearts of his brothers – the moment to reveal/expose his vulnerability, humanity, dignity), with reference to providence, what we might call big-picture creativity.

The dream produces a certain poetry. “God sent me before you to preserve life … Even though you intended to do harm to me, God intended it for good …” “Love your enemies … lend/give … expect nothing in return”, which may also be rendered, “Do not give up on anyone” (the Greek text is richly layered).

Theo-poetics inspires theo-praxis. Do good. Bless. Pray. All of this in the context of creativity – the experience of Creation as giving, giving first, for-giving, grace.

“I am Joseph.”

“Love your enemies.”

“This is my body, given for you.”

The mystery of faith entails a grateful receiving/taking (appropriating, incorporating the gospel), but, more deeply, a thanksgiving (eucharist). As Jesus says: “The amount you measure out [give] is the amount you’ll be given back.”

Scholars ponder this and other “hard sayings” of Jesus. These are, indeed, bold words. Sacramental. It seems to me that fundamentalism of whatever kind adopts a passivity when it comes to faith – promotes a passive or consumer religion.

Jesus, like Joseph before him, reverses this. His gospel is not about answers, slogans or doctrines readily consumed, so much as evocations, provocations, vocations – bold invitations to for-give, to give meaning, to give one’s life with and for others.

To join with Joseph, saying, “I am Greg” … saying, “I am Norrie … I mean you no harm …” To join with Jesus, the Lamb of God committed to breaking cycles of fear, blame and retaliation.

We have another artwork by Sister Corita today. “Hope” in the Spirit of a God who reverses expectations of rough or retributive justice. I really like the words (a quote from poet and educator Ned O’Gorman) reversed out of the orange: “The secret is to risk disaster, hope for triumph, and describe the forms of the Incarnation.”

The dream is the call. Faith is risk/adventure. Salvation/happiness is “yes” to invitations to love. Making the impossible possible. Embodying the divine. Inter-carnation.

And not just any dream will do.

French Cistercian Father Christian de Chergé, kidnapped and murdered by Islamic fundamentalists, had long encouraged Islamic-Christian dialogue. With Muslim scholars and friends he prayed to the God of compassion. He spoke Arabic, Latin, Greek and Hebrew.

Three years before his martyrdom in Algeria in 1996, Father Christian wrote a letter “wholeheartedly forgiving whoever [his] killer might be” and praying “may we meet each other again, happy thieves, in paradise, should it please God.”

The dream of reconciliation and the dream of peace, God’s dream, invites our full participation, for Christ’s sake.

It will mean something like turning the other cheek in the sense of reversing expectations of retaliation, revenge. It will mean daring to face an abuser (daring to expose/reveal a common vulnerability, humanity, dignity – a deep-down goodness) – an accurate paraphrase of turning the other cheek – though not in every situation, and rarely, if ever, on one’s own.

Reversing expectations of revenge, making love happen, describing the forms of the Incarnation – all this we are called to do together.

“I am with Joseph. We mean you no harm. We desire the happiness and wellness of all.” Amen.