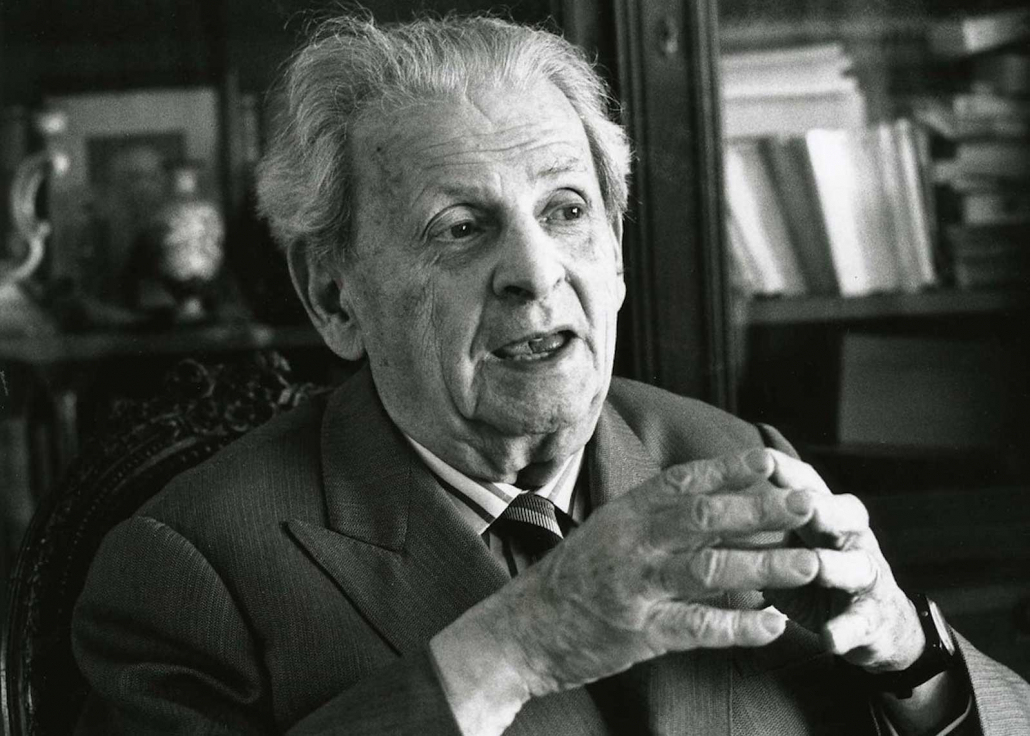

Emmanuel Levinas.

Photo: Bracha Ettinger

‘Pure-heartedness means more’

Andrew Collis

Ordinary Sunday 22, Year B

James 1:17-27; Mark 7:1-8, 14-15, 21-23

Jesus says to those he calls hypocrites: “You disregard God’s commandments and cling to human traditions.” The examples he gives indicate that divine commandments have to do with showing genuine honour/respect; with cultivating fidelity, kindness, generosity, honesty, humility, wisdom.

In company with the prophet Isaiah, and with James the Just, Jesus calls for ethical expressions of faith.

Rituals are of value in the service of moral and ethical development. Clean hands may express concern for others (hand hygiene is very important, of course). Pure-heartedness, though, means more. Pure-heartedness means coming to the aid of others in their vulnerability.

Charles and John Wesley, and Methodism at its best (I heard an inspiring interview with the Rev. Bill Crews on the radio last week), emphasise the same point.

I also think of Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas (1905-1995), for whom the other is not knowable and cannot be made into an object of the self. Levinas prefers to think of philosophy as the “wisdom of love” rather than the “love of wisdom”. In his view, responsibility toward the other precedes any objective searching after truth.

Ethics is “first philosophy”. And the ethical obligation emerges when we apprehend the face of the other.

“The skin of the face is that which stays most naked, most destitute,” he says in a 1982 interview, published as Ethics and Infinity. “The face is exposed, menaced, as if inviting us to an act of violence. At the same time, the face is what forbids us to kill.” This instantaneous shift – we see the potential for violence but then immediately shrink from it – is the original source of ethical obligation.

“There is a commandment in the appearance of the face, as if a master spoke to me,” Levinas says. And the face he is describing is always real, never a metaphor; faces – especially the faces of strangers – actually matter.

Pure-heartedness, the wisdom of love, means more …

Perhaps, then, we learn to be critical of arrogant claims to pure religion. Gary Bouma reminds us that vital religious movements evince a mixing of elements; borrowing has long been the order of the day “at least since those who compiled the book of Genesis borrowed pre-existing creation stories and adapted them to its purpose” (Australian Soul, 2006).

Pure-heartedness entails a certain impurity, something relational – entanglement.

So perhaps we learn to love other than human faces. “[E]thics follows from how we experience the world”, writes Norwegian philosopher Arne Næss, who urged the green movement to “not only protect the planet for the sake of humans, but also, for the sake of the planet itself, to keep ecosystems healthy for their own sake”.

Pure-heartedness, the wisdom of love for the world, can lead to a different conception of ethics, one that circles less around principles of moral obligation and that instead concerns our dwelling within the world.

Every living being has an intrinsic value which is not quantifiable. Every other “has a right to live and blossom” (Næss).

Jesus says to those he calls hypocrites: “You disregard God’s commandments and cling to human traditions.” The examples he gives indicate that divine commandments have to do with showing genuine honour/respect; with cultivating fidelity, kindness, generosity, honesty, humility, wisdom. Amen.