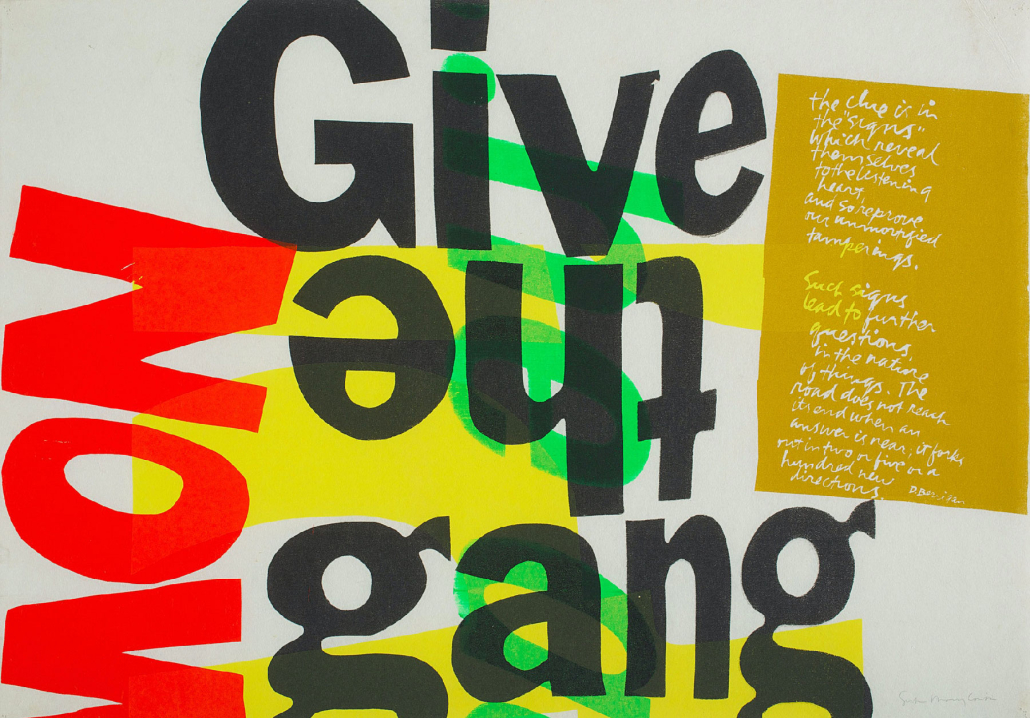

Image: Corita Kent, ‘(give the gang) the clue is in the signs’, 1966.

‘Soulful rest’

Andrew Collis

Ordinary Sunday 14, Year A

Genesis 24:34-51 (52-67); Psalm 45; Matthew 11:16-19, 25-30

Today’s gospel – good news for the anawim or “have-nots” (11:5) – invites a number of responses. We might respond to the image of the yoke, a farming implement for working cattle, a symbol of Wisdom/torah/teaching. We might respond to the image of Messiah as co-worker. We might respond to the theme of rest or sabbath, by way of comparing/contrasting Jesus and John the Baptist, Jesus and the overtly religious, penitential and self-righteous community. God be with you …

To yoke is to join, to join forces. The gospel assumes there is work to do; there are wise and foolish ways to work.

According to Matthew, chapters 11 and 12, the work entails healing and liberation; resisting destructive forces; discerning Wisdom and kinship amid irreverence/disrespect.

The Rev. Thresi Mauboy, former Moderator of the Uniting Church Northern Synod, comments: “So often, the wisdom and authority [of Aboriginal Elders] was dismissed by governments and churches …” On behalf of Elders, she asks: “How long do we need to keep telling the stories of land and loss … cultural richness and justice … for the voices to be heard?”

Perhaps the most foolish way to work, it would follow, is alone (separate from others, neglectful, disdainful, resentful …).

We might think of supplementary images.

Spiritual and bodily exercises (the word “yoke” is related to the word “yoga”) …

Musical collaboration and improvisation …

Walking and working side by side …

“When we honour our Elders, we are also honouring a part of ourselves, the part that is connected to these respected people through gurrutu skin relationships, those with us in person here and now, and those that are eternally with us in spirit” (Thresi Mauboy).

Welcoming the other (human and non-human) in and through whom divine assurance speaks. Receiving the other (human and non-human) who enables prayer and ethical practice.

To be yoked to Wisdom/torah/teaching is a good thing. Rabbi Jesus is stressing what this means. It means engaging God and serving others. It means getting to know the Earth. It means caring, committing and discerning. Sharing burdens.

Of course, then as now, religion is all-too burdensome.

We might summarise the burdens of religion in terms of self-righteousness (“vain ambition”), moralism (finger-pointing and handwringing) and sectarianism (which limits the reign of love to one or other small kingdom).

We might ask which groups in our society tend to be most burdened by religious vanity and moralism – those least able to bear the burdens of guilt, shame, hopelessness. Who are the victims of sectarianism – made afraid of difference, afraid to disagree?

We might extend our thinking on religion to include the dominant religion of capitalism which divides human communities, isolates human beings and reduces persons to consumers, addicts enslaved not only to sticky drinks (I used to work at a fast-food restaurant so I know how heavy those bags of syrup are!) but to the false promises of sticky drinks – the false promise of “fun”, “health”, “life”, and so on.

Artist Corita Kent’s peculiar genius was to draw life-giving wisdom from slogans and trademarks. The phrase “give the gang our best” started as a greeting, flattened into an advertisement (for Canada Dry), and through a creative process prompts us to think about generosity and the unexpected grace that flows between friends/peoples.

What does it mean to give to those we care about? What does generosity look like outside of the decaying habits of capitalism? What exactly is our best and how do we access it?

To be yoked to Wisdom/torah/teaching is a good thing. Rabbi Jesus is stressing what this means. It means engaging God and serving others. It means getting to know the Earth (profound intimacy). It means caring, committing and discerning. Sharing burdens.

The theme of soulful rest relates to sabbath observance. Matthew’s Jesus is keen to enrich sabbath observance, making room for lament (in the tradition of the prophets, including John the Baptist), for open table fellowship (all manner of refreshment), for compassion and healing (Jesus cites Hosea 6:6).

Do good, in other words (12:12). Do something good on the sabbath.

For restfulness is more than the mere cessation of work. It means forgetting work in the name of love (in the name of an ungraspable other – as poets and lovers well understand). Restfulness means forgetting work in the interests of knowing wisely when to listen, when to speak, when to draw close and when to draw back.

Writing in the 1950s, theologian Paul Tillich said that responding to the call of Jesus means openness to what Jesus offers – New Being. “We spread [the] call because it is the call to every [person] in every period to receive the New Being, that hidden saving power in our existence, which takes from us labour and burden, and gives rest to our souls.”

In such a mode, we repent in the sense of turning to goodness, returning to God. Amen.