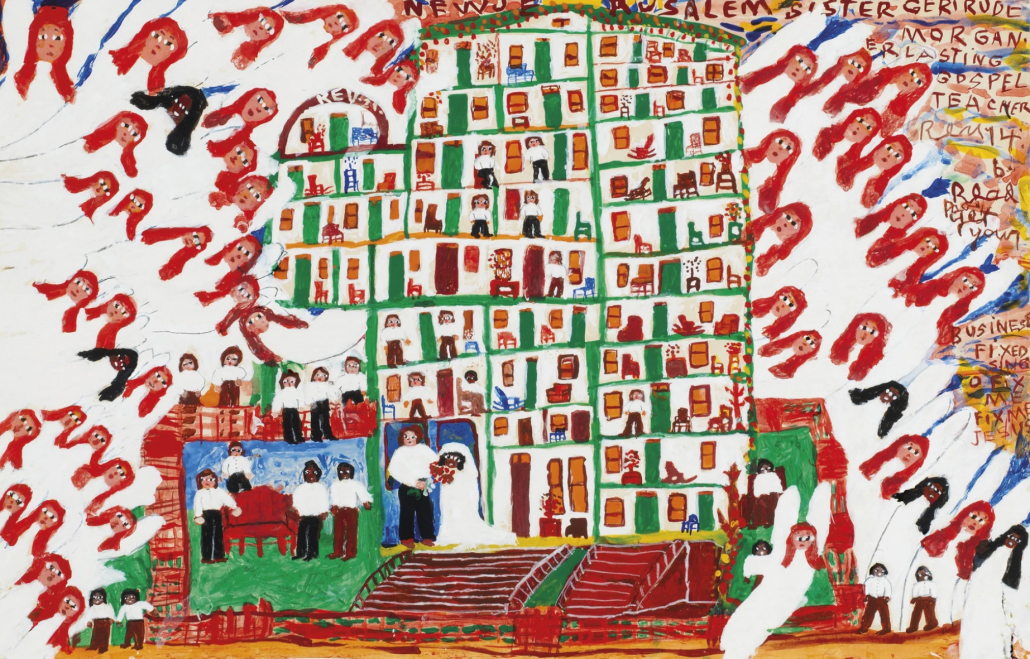

Image: Sister Gertrude Morgan, ‘New Jerusalem: Get Your Business Fixed’, c. 1970; acrylic, graphite and ink on thin card.

‘Sustained by a vision’

Peter Walker

Easter 6, Year C

Revelation 21:10,22 – 22:5; John 14:23-29

When I was 20 years old, I heard Nelson Mandela speak in Sydney at a prayer service for the people of South Africa. It was one of the most moving occasions that I can recall because it was, for me, the first time I truly realized what it means for someone to be sustained by a vision of what might be. And it was also the first time that the book of Revelation meant anything to me at all. I will come back to that book.

As a university student I had sat up all night, just months beforehand, to watch for Nelson Mandela’s release from prison. It was 11 February 1990. Mandela, as you know, spent 27 years in prison. The service of prayer where I heard Mandela speak was held in St Mary’s Cathedral, in the centre of Sydney. I am still surprised I was even there. I confess I was an un-prayerful person at the time. But I am very glad I changed my ways for that occasion. And I still consider it something of a treasure that I gained his autograph that night.

What is special for me about that memory, and why I am telling this story, is that one of the readings for the service on that evening, now 32 years ago, led me into an experience of hope. It was from Revelation chapter 21:

Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth,

for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away…

And I saw the holy city, the new Jerusalem,

coming down out of heaven from God …

And the city has no need of sun or moon to shine on it,

for the glory of the Lord is its’ light …

Then the angel showed me the river of the water of life,

flowing from the throne of God …

On either side … was the tree of life …

and the leaves of the tree are for the healing of the nations.

(Various verses from Rev 21)

Mandela spoke. An African choir sang. Sang with the kind of emotion that draws your breath away. And, no doubt, magnificent prayers were offered. But I was deeply struck by two things. The words of the author of Revelation, who we believe to have been the disciple John, who was at that time a prisoner on the Island of Patmos, and not far in time from his own death. And the other was the words of Mandela, who had spent 27 years as a prisoner on Robben Island.

I watched Mandela. I listened to his journey. I heard his own experience of sustaining faith. I heard him speak about transformation in South Africa. And I heard alongside that South African experience, I hope not naïvely, John’s vision of a world made new – not only with the hearing of the ears; I really heard it.

And then I saw a new heaven and a new earth.

A holy city with a tree at the middle.

And the leaves of the tree are for the healing for the nations.

I found myself disarmed of my cynicism that religion, and the Christian faith, and biblical books like Revelation, were about securing a ticket to an afterlife. Instead, I was hopeful that transformation in the present might be what God is on about. This energising desire for change is the experience of hope.

….

The author of the Revelation has given us a good example of how human language is incapable of expressing hope without an imagination that transcends things as they are. This is very much the role of the apocalyptic texts that one finds in the Christian Bible (and in the religious texts of other traditions). Most sacred texts are in fact bifocal. In the near lens they address things here and now. In the far lens, the language shifts. Human imagination is incapable of perceiving, the reality of things eternal, but most sacred texts try.

Rather than being paralysed by the finitude of human language, John is set free by his inspired imagination to portray the hope of the Christian tradition in a variety of human images. The idea of a heavenly Jerusalem, for example, that would become the ultimate home of humanity. This is not a reporter’s description of what he saw. This is literature composed as a means of expressing what John believed to be the nature of God’s hope for this world. It is fantastic language, in the best sense of that word.

What did John think we needed to know about that which we hope for? Two things, in particular.

In John’s vision God says, “See, I am making all things new” – not “all new things” (Rev 21: 5). It is this world that God cares for and seeks to transform. It will not be replaced by a different “new” world. A Christian understanding of hope drives us toward the renewed life of all that is here and now. The planet and all life is not disposable.

And, secondly, John gives very moving expression to the Christian conviction that in the end we meet, not an event, but a person. In the end, there is God. There is no temple, because there is no longer the need for a special place, or a special time. God will be “all in all”. “I am the alpha and the omega.” God does not merely bring the end; God is the end. John’s first and last word is God.

….

The Bible not infrequently points us, in texts like this one, toward a world “not yet”. A world still on the horizon. “A world made new.” I used to think this was day-dreaming. An escape from reality. Now I think these religious visions, this religious imagination and the hope they inspire, are more important than anything else in driving a change toward justice and a renewal of life. Hope marks the end of our adjustment to what is; and the genesis of our living for what might be. “I have a dream”, said Rev Dr Martin Luther King Jnr. He understood hope and its connection to “the healing of the nations”.

It is human nature to act within the parameters of what we perceive to be possible. If we see only what is, we act only within the rules of the here and now. But if our eyes are opened to a hope beyond what is here and now, the parameters of our actions will also be enlarged. All good religion will do this. In the Christian imagination, that hope enables us to find the will to see the holy city, and the river of life, and the healing of the nations.

And so, this is why I remember Nelson Mandela speaking of how his vision for a just South Africa sustained him through those 27 years of imprisonment and inspired his struggle. From within the parameters of Apartheid South Africa, what hope could he have had? And what hope could Martin Luther King have had within a legally segregated United States? Yet, their hope for what might be, hope beyond the parameters of the here and now, enabled them both to lead extraordinary change.

What about ordinary people like you and me? Throughout the Bible whenever there is a reflection on what God is doing for us, there is always an implied imperative. The gift always becomes an assignment. If a renewed creation, represented by the holy city, is God’s hope for creation, then it becomes the hope and task of the Christian church.

The Christian will ask (I hope!): What will this vision enable me to achieve for those who live in darkness; for those to whom the city gates are shut; and for the healing of the nations? In the Christian tradition, hope is not only about a vision of the future. It is also, and more so, a call for action, justice, and renewal in the present. May that become our hope too. Amen.

The Rev. Dr Peter Walker is Principal of United Theological College.