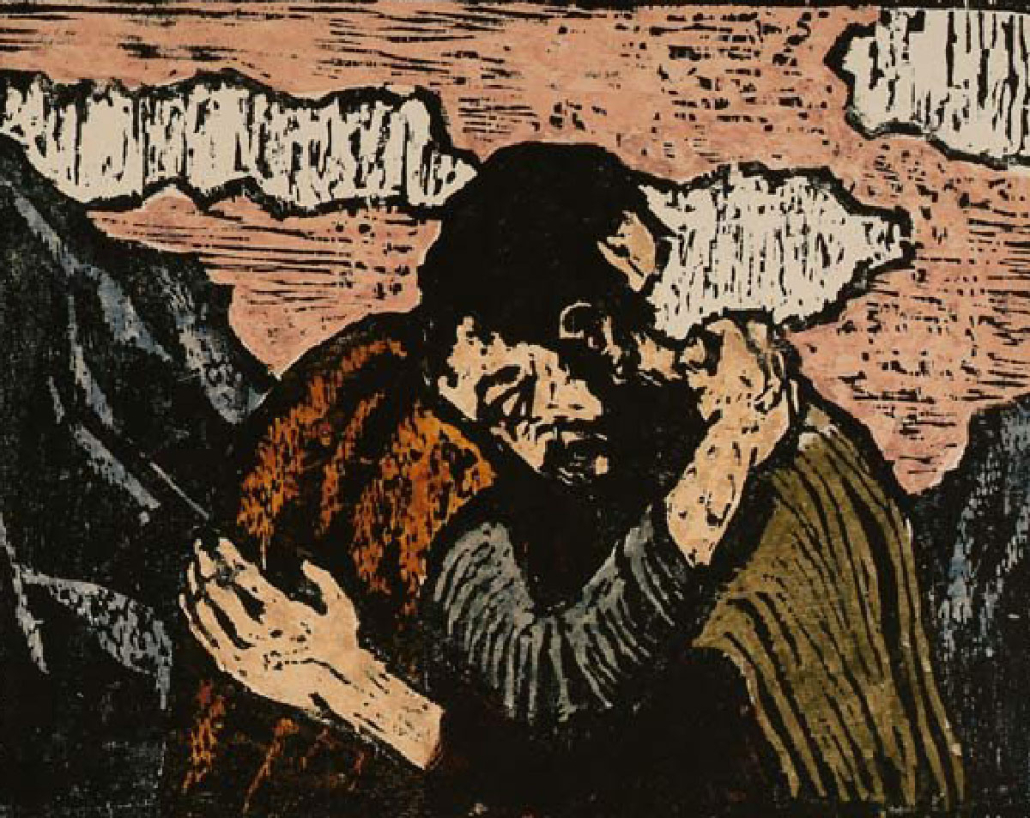

Image: Jakob Steinhardt, ‘Jacob and Esau’, woodcut, 1950.

‘Wounded healers’

Andrew Collis

Ordinary Sunday 18, Year A

Genesis 32:22-31; Matthew 14:13-21

American philosopher Judith Butler, whose interests include literature and feminism, and whose recent work focuses on Jewish philosophy, exploring pre- and post-Zionist criticisms of state violence, writes: “Let’s face it, we’re undone by each other. And if we’re not, we’re missing something.”

What strikes me on hearing again this story of Jacob wrestling with the angel/stranger is the fact that Jacob is struck upon the “hip” – struck at the centre of his being – and that he is changed, blessed, re-named, and walks thereafter with a limp. Jacob is blessed and wounded.

Israel is wounded and blessed. He has learnt something important enough to warrant a name change, and it has to do with conversion from scamming and swindling (Jacob means “Heel-Grabber”) to struggling with God and others in the name of forgiveness and reconciliation.

In the very next chapter we read that Jacob/Israel went on ahead and bowed to the ground seven times as he approached his brother Esau. But Esau ran to Jacob/Israel and embraced him, throwing his arms around him and kissing him. And they wept.

Wounded and blessed, estranged siblings embrace and weep.

Is this the way it is for us?

Do I learn compassion in the wake of struggle, as I face my fears (of isolation, contagion, inadequacy, failure), and as I learn that God is present in the one so very like myself, the one I thought my rival, the one I have cheated or harmed (shunned or shamed), the one who knows me well and names me?

Sometimes I’d rather simply know for myself, by myself, within myself, how to be compassionate, how to love, without having to struggle or suffer, without my being so exposed, so porous. I’d rather be a strident and confident healer/teacher, not wounded and limping.

Our gospel reading shows us that for Jesus, too, there is struggle in respect of identity and vocation. He has just heard about the execution of his cousin John, with whom he has shared so much. He seeks a “deserted place to be alone”, presumably to grieve.

And, amid mourning, he is moved to compassion for those who have followed him from the towns. Another of Butler’s lines rings true: “Loss has made a tenuous ‘we’ of us all.”

Chris often reminds me about the good work of the Rev. Bill Crews, a long-running Loaves and Fishes restaurant and a long-running Sunday night radio program.

The “radio reverend” listens and tells stories, bearing witness to healing by way of word-touch, a double transformation of incurable wounds into healable scars. “[S]uch healing is to be understood in a very specific manner – not as facile closure or completion but as open-ended story, namely, as a storytelling that forever fails to cure trauma but never fails to try to heal it” (Richard Kearney).

The “feeding of the five thousand” (there are six versions of the story in our gospels – no doubt it was a crucial story for the early churches) serves as a model of ministry, a model of compassion, sharing what is needed for life from the depths of human woundedness.

The miracle looks back to God’s providing manna for hungry wanderers in the wilderness, to the institution of the Eucharist (Christ’s offering the very life of God in and through his own life), and toward the final consummation of God’s reign in which all people will be gathered and blessed at the banquet table.

The gospel shows us that Jesus pleaded with Abba-God for an alternative to suffering love. And yet the Christ we call Sovereign and Risen is a Saviour forever scarred, forever wounded.

Drawing on the work of Judith Butler, one theologian describes the gathered assembly thus: “A crowded, haunted collection, folded into the God folded into us, interrupted and undone by each other, we desire, mourn, and remember” (Mary-Jane Rubenstein).

Before concluding, I note that Jesus both tells and enacts parables (invites us to both tell and enact parables). The kindom of heaven is a poetics, a theo-praxis. A minister of word and bread, Jesus makes story-pictures and distributes good news – timely, tactile, tasty …

I think about the South Sydney Herald, too, as good news distributed (the gospel in journalistic mode). Theo-praxis in place, of place. It’s one thing, for instance, to say we support the Uluru Statement and a Voice to advise parliament and government. It’s another to (delight in opportunities to) amplify Aboriginal voices, Indigenous wisdom. To lend a hand, to have a hand in the process, to help hand out testimonies and commentaries (as Norrie hands out 2,000 papers each month) …

Let’s hand them out now …

On page five of this month’s SSH, we read the story of artist Michelle Blakeney …

Drawing on the work of Judith Butler, one theologian describes the gathered assembly thus: “A crowded, haunted collection, folded into the God folded into us, interrupted and undone by each other, we desire, mourn, and remember.” Amen.