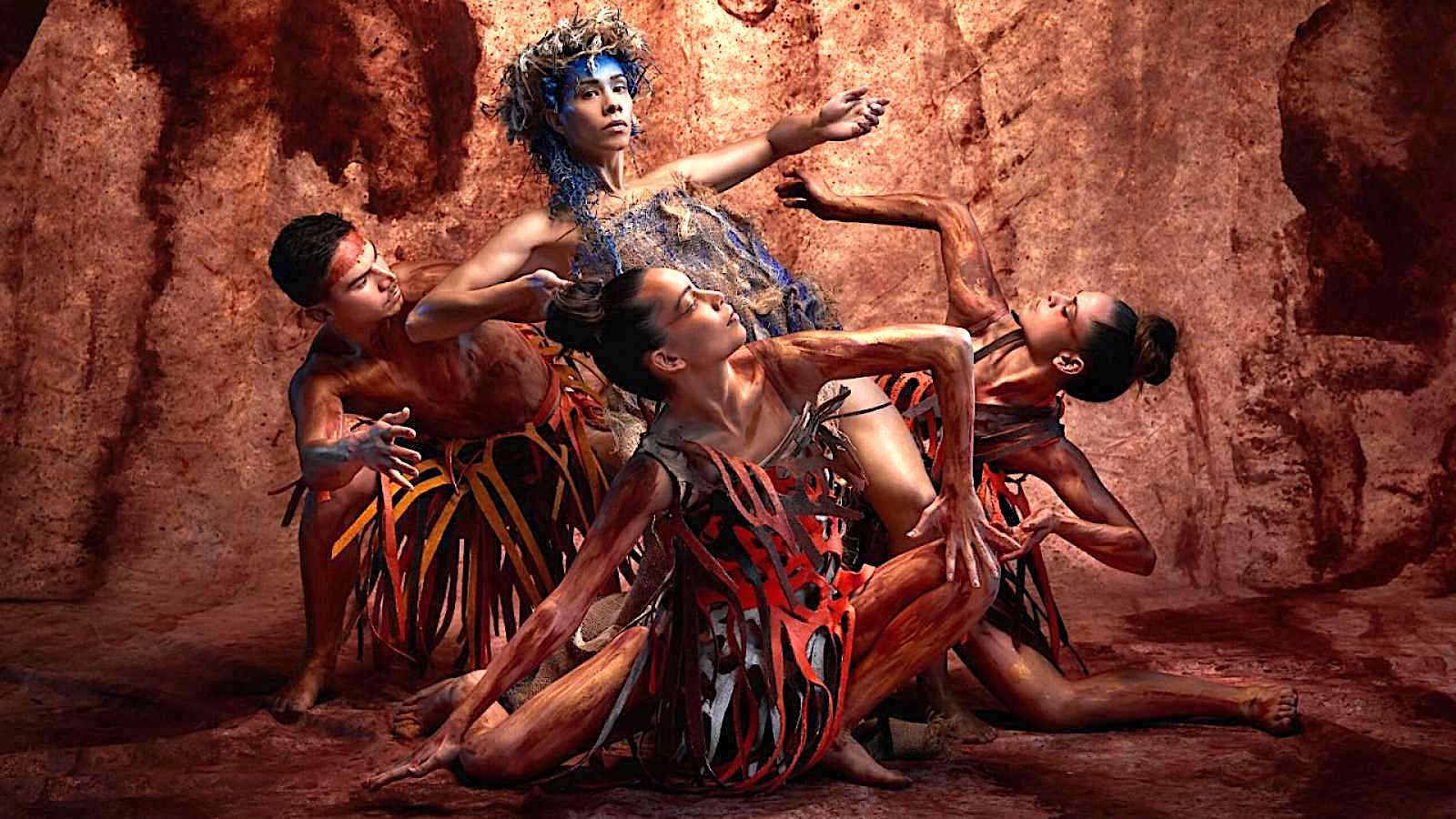

Bangarra, ‘SandSong’.

Photo: Daniel Boud

‘Write, sing, dance’

Andrew Collis

Ordinary Sunday 15, Year B

Mark 6:14-29

Standing up for what’s right and compassionate is to risk/live your life. Paranoid powers – gluttons and abusers like Herod – deeply resent social and political criticism, and prophets like John the Baptiser are undermined, ridiculed, imprisoned.

In the context of Mark’s gospel, the execution of John foreshadows the crucifixion, which will see Jesus the prophet in agony, abandoned by the Twelve, buried by a stranger. How noble, then, that John’s disciples “came and took [John’s] body away and laid it in a tomb”.

Dorothy’s table setting features a microphone tied with rope to the cross – a symbol of binding and silencing on the part of those in power. We might think of our own government’s efforts to censor charities that dare to criticise lawmakers or encourage protestors. “The Morrison government should be supporting charities and welcoming our advocacy, not threatening us with new rules that could shut us down for speaking out,” says Alice Drury, a senior lawyer at the Human Rights Law Centre.

The contemporary icon of Amos depicts a prophet from the time of the divided kingdoms (800 years before Christ). Amos was a shepherd and farmer, unschooled and not one of the professional prophets of his day. He lived in the southern kingdom of Judea, in a town south of Jerusalem, where he experienced a call to go north. The king of the northern kingdom of Israel was Jeroboam, and Amos prophesied against the impiety and injustice of Jeroboam’s rule.

The prophet predicted (rightly as it turned out) that it would all end badly for the greedy and the violent. He was beaten and tortured for his troubles, struck on the head by an angry priest, before making his way back home where he succumbed to his injuries.

This is all hard to look at. And hard to bear. Scripture, writing, icon-writing, is one way to bear it. Which also means bearing witness.

In 1998 Paul Kelly penned a song called “Little Kings”: “I’m so afraid for my country/ …Every day I hear the warning bells/ They’re so busy building palaces/ They don’t see the poison in the wells/ In the land of the little kings/ Profit is the only thing/ And everywhere the little kings/ Are getting away with murder …”

It’s a song about Australia. In the context of a gospel about dancing, I think of the Bangarra company – bearing noble witness to love of country, kinship, survival.

In her review of Bangarra’s recent production SandSong, the South Sydney Herald’s theatre editor Catherine Skipper writes:

“[T]he performance begins by delivering a shock – harsh sounds and a grim dark backdrop – to its comfortably seated audience … Uncomfortable facts are set before us …

“[T]he back-drop reflects the gold of the sun, the red of the desert dust and the rolling motion of the full Bangarra ensemble – and the circle inscribed beneath their feet – invoke the cycle of unfolding seasons that sustained life. A shy young woman and an uncertain young man are inducted into their respective roles and their place affirmed: a traditional dance for women images the ritual of providing, the man’s traditional dance tells a story of rightful possession of the totem or keeping order.

“This lovely image of an established way of life carefully calibrated to maintain a balance between people and land is threatened …

“[T]he living seasonal cycle has been replaced by a relentless and deathly cycle of work – with barely enough rations – but the land itself will rescue them from the dark times. The welcome voice of Vincent Lingiari is heard, a voice that reminds them that the land is their land, and that they want to live on it their way.

“[I]n a touching interlude, a lost young man can still be reconnected with the code of life handed down through his ancestors and is restored by the spirit of the land, who ritually and lovingly cleanses and heals him. Pride reawakened, a lost and abused people reunite and revive. Rituals can be recovered as tenderly conveyed in the woman’s traditional potato dance, and painting Country restores them to homeland, community and family.

“In the ultimate scene the ensemble comes together to affirm their belonging, and separating into groups, they fold gracefully into each other, serene and breathing in accord with the spirit of their land. We are left with the conviction that the ancient knowledge of People and Country can be dispersed, but it can never be lost. SandSong itself is living proof, created by Bangarra in consultation with Wangkatjungka and Walmajarri Elders and Cultural Knowledge Holders from the Kimberley and Great Sandy Desert regions” (https://southsydneyherald.com.au/sandsong/).

And so, we lament. We write, sing and dance – review, protest, create. Aware that every strong and hopeful word (including the Word of God, of course) is hard won (words become flesh become words become flesh), we celebrate together what is good and noble. Amen.